Prisoners and/of War

December 2005 Author:Dan Pinck

Question: Which nation dressed soldiers as monks to enter a city and kill civilians, including hospital patients?

Question: Which nation conducted human vivisection, biological warfare, and used a crematory?

Question: Which nation killed more than a third of their prisoners of war?

Question: Which nation trained young, school-age girls to carry explosives in school satchels to use in blowing up enemy vehicles and in the process killing themselves?

The answer to all of these questions is Japan, a fact that grows dimmer in our knowledge with each passing year. Japan has never formally accepted its guilt, aside from a few perfunctory apologies. Japan has never admitted its atrocities and it is unlikely that it ever will. On a visit to Great Britain in 1968, Emperor Hirohito allowed his interpreter to say, “The Emperor is sorry.” A Prime Minister of Japan, Tomiichi Murayama, offered many years later his “heartfelt apologies” for his nation’s actions, mainly directed at causing physical damage and destruction to other nations in Asia. In a recent article in The New York Times about a group of goodhearted Japanese who toured a few wartime horror sites in Manchuria, a visitor said, “We Japanese have never been able to say we made a mistake.” Caught in an ethos of savagery during the war, the Japanese considered themselves as victims after the war ended.

I reveal a glimpse about myself and my interest in this subject before I immerse you in a varied though selective portion of Japan’s record of its treatment of prisoners of war. Few weeks go by when I don’t recall my experiences in China during the Second World War. As a sole American representative of the Office of Strategic Services, I served behind the lines in Japanese-occupied territory in Kwangtung Province, up the coast from Hong Kong. I employed about forty Chinese agents who gathered military, naval and political information in Japanese-held coastal towns. I was selected for this activity because I was too young (I was twenty-one) and inexperienced to be overly scared at being surrounded by Japanese forces. In fact, I wasn’t scared until a Chinese agent whom I knew was captured by the Japanese. After a few day’s captivity, he was forced to dig his own grave and he was buried alive in it. Thereafter, I slept with a .45 pistol. I carried two .45s during the day as well as a suicide pencil. I decided that I would probably use my suicide pencil if capture by the Japanese seemed imminent. Japanese soldiers regularly marauded for food in my area, killing Chinese farmers and raping their wives and daughters. My war ended sixty years ago, but my memories of it are still vivid.

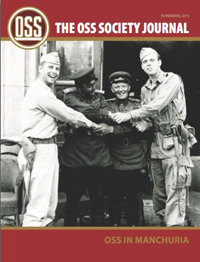

Japan began its war against China on September 18, 1931, invading Manchuria with an army of 200,000. They took control of Muken in a four hour battle with Chinese forces. In Mukden and other locations, they took no prisoners. Instead, they killed soldiers and civilians with abandon. This initial action was a preview of how Japan would fight in Asia and the Pacific for the next fourteen years.

Our Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson protested and Japan acceded to a temporary peace accord. The League of Nations began studying the situation. It sent an investigative team to Manchuria headed by Viscount Lytton of Great Britain with members representing the United States, Great Britain, France, Germany and Italy. The team’s report that called for Japan to leave Manchuria was passed by the League by a vote of 42 to 1. Result: Japan remained in Manchuria, the industrial heartland of China. No nation intervened. The League of Nations exhibited its impotence.

Representatives of Emperor Hirohito signed the International Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, in Geneva, on July 27, 1929. Since the Japanese Parliament did not ratify the Convention, they had no legal obligation to abide by it, not that it would have, in any event. Beginning in Manchuria, the Japanese record in killing prisoners and civilians never abated, without change or remission, for the following thirteen years. Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere began its work without remorse or pity. Murder is murder: an inclusive policy was followed subsequently in Burma, Thailand, Malaya, Indochina, Singapore, Formosa, Hong Kong, New Guinea, Korea, Borneo, Sumatra, the Philippines, the Netherland East Indies, in Japan itself, and throughout the Pacific.

An experimental biological warfare program was initiated by the Japanese in Manchuria in the early 1930s, under the command of an Imperial Army physician, Lieutenant General, Shiro Ishii. At Ping Fan, a village near Harbin, the general and his staff constructed a facility for human experimentation and extinction, complete with laboratories and a crematory with a tall mast of a chimney like those at Auschwitz. The crematory was photographed during the war; at war’s end, it was destroyed by the Japanese. The facility was named Unit 731. In other war areas, outside Manchuria, it was called Unit 100, with operational bases in other areas and nations throughout the war. But Unit 731 was the precursor, and it conducted its work on civilians, soldiers and prisoners in Manchuria. The Unit killed thousands of Chinese and Russian residents in Manchuria, in and around Harbin and Mukden, some of them subject to vivisection. Sheldon H. Harris, an American historian, whose book, Factories od Death: Japanese Secret Biological Warfare, 1932-1945, and the American Cover-Up, recounts his twenty years of research into Japanese biological warfare in Manchuria and occupied China. He estimated that 250,000 civilians and 10,000 to 12,000 prisoners of warfare were killed. This number seems excessive; but, since no one else made eleven trips to China doing research on this topic, we’ll let it stand. The American cover-up relates to the fact that we wanted the Unit’s data (200,000 pages) for our own biological warfare experiments. We gained the data. Not a single member of the Unit was charged as a war criminal in the Tokyo trials. Two hundred Unit members were tried and convicted by the Russians in a war crimes trial in Siberia after the war.

More than a recondite footnote, it is pertinent to note that the Russian army killed 70,000, or more, Japanese troops in an incursion that the Japanese made in 1939 into Mongolia. The Russians employed planes and tanks.

Once the Second World War began, on December 7, 1941, Japan opened two major prisoner of war of camps for Americans in Mukden. Many American POWs were killed by staff members of Unit 731. American POWs from as far away as the Philippines were sent to Mukden, including General Wainwright, McArthur’s deputy, whom he had left in the Philippines.

On July 7, 1937, Japan began its invasion of China proper at the Marco Polo Bridge, near Peking. At the time, the Chinese government called this the War of Resistance and again appealed for help in stopping Japanese aggression. Our Secretary of State Cordell Hull delivered A speech on July 14, 1937, advocating international justice and Avoidance of the use of force as an instrument in promoting national Policy. Result: nothing happened. China also appealed to Great Britain for help. The British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlin, adopted his first appeasement policy, toward Japan. His priority was to maintain British interests in the Far East. Result: nothing happened. Four years later, the Second World War began at Pearl Harbor, and China became our ally in the all-out war against Japan.

Japan operated more than 250 prisoner of war camps throughout Asia and the Pacific. Japan’s treatment of prisoners of war of all nations is beyond imagination. It’s my desire to limit this account to selected incidents, to delineate the context in which many deaths occurred, and not to try to convey the entire, bloody record in detail. Still, the record is gruesome; it can be neither hidden nor minimized.

Emperor Hirohito approved the following order that was written by The Minister of War, the only Cabinet member who had direct access to him. It was sent to all commanders of POW camps and to the chiefs of staff in all areas. It was transmitted to them on August 1, 1944 by the Vice Minister of War. By the summer of 1944, we and are allies were starting to make progress in the war, and the Japanese knew it.

Under the present situation if there were more explosion (sic) or fire

a shelter for the time being could be had in nearby buildings such as

a school, a warehouse, or the like. However, at such a time as the

situation becomes urgent and it is extremely important, the POWs will

be concentrated and confined in their present location and under

heavy guard the preparation for the disposition will be made. (sic)

The time and method of this disposition are as follows:

The Time.

although the basic aim is to act under superior orders,

individual disposition may be made in the following

circumstances:

When an uprising of large numbers cannot be

surpressed without the use of firearms.

when escapes from the camp may turn into a

hostile fighting force.

(2) The Methods.

Whether they are destroyed individually or in

groups, or however it is done, with mass bombing,

poisonous smoke, poison, drowning, decapitation, or what,

dispose of them as the situation dictates.

In any case it is the aim not to allow the escape

of a single one, to annihilate them all, and not to

leave any traces.

An example of this order occurred in 1944 at a POW camp at Palawan in the Philippines. When an American plane appeared, the commander of the camp, whose American prisoners were building an airfield, rounded them up, put them in air raid shelters, and ordered his troops to pour gasoline over the shelters and ignite them. A few Americans who escaped from the shelters were shot. Nine men survived by jumping into the sea and swimming to a nearby island. One hundred and fifty Americans were burned to death. At a POW camp on Bangka Island, off Sumatra, the Japanese bayonneted twenty-one Australian nurses. This happened in 1942. In 1944, the Japanese killed American airmen at Truk, including the beheading of a U. S. Navy radioman. The radioman was then cooked and eaten. Dr. Chisato Ueno and Lieutenant General Joshio Tachibana and eleven others were and executed at a war crimes trial for the beheading and cannabalism of U. S. Navy airmen. More than 125 Americans were beheaded during the war. An Indian prisoner of war in New Guinea said at a war crimes trial, “At this stage the Japanese started selecting prisoners and every day one prisoner was taken out and killed and eaten by the Japanese. I personally saw this happen and about one hundred prisoners were eaten at this place by the Japanese. Those selected were taken to a hut where flesh was cut from their bodies while they were alive and they were thrown into a ditch while they were still alive and where they later died. While flesh was being cut from those selected, terrible cries and shrieks came from them and also from the ditch where they were later thrown.”

Using war crime records, Michael Goodwin wrote a book, Shobun: A Forgotten War Crime in the Pacific, about an American bomber crew whose plane crash landed in Japanese territory. The crew, of which his father was a member, was captured and then beheaded. Shobun means execute. The Sandakan Death March was aptly named. In the first death march, in January 1945, some 2,000 to 3,000 prisoners, mostly British and Australian, were killed. Their Japanese captors expected an invasion. In the second death march, in June and July 1945, six prisoners survived out of a total of almost 2,400.

American prisoners of war totalled 21,580. The number of them killed by the Japanese was 7,107, representing 32.9 percent of those held captive. The total number of Allies, including Americans, in POW camps was 140,000. Roughly 35,000 were killed. Ninety percent of the Burmese andThai prisoners were killed. In the European Theater, 1.3 percent of American prisoners in German camps were killed. The notion that Germany was any less brutal than Japan in its treatment of prisoners is dispelled by the fact that of about 2,800,000 out of a total of 7,800,000 Soviet prisoners died in Germany.

It is difficult to gain an accurate or even an approximate number of the total number of Japanese prisoners of war. General George C. Marshall estimated that there were 41,464 Japanese prisoners. The International Committee of the Red Cross recorded 15,849 prisoners. A Japanese historian, Ikuhiko, claimed there were 50,000 Japanese POWs, including those in China. Another historian, Ikeda Kiyoshi, estimated that there were about 20,000. Slightly more 200, he reported, were killed without provocation; that is, without uprisings in POW camps.

The difference in figures, while not unusually varied, is revealing overall for the small number of Japanese who surrendered. Surrender was not in their vocabulary or their military culture; besides, Japanese troops knew nothing about the Geneva Conventions dealing with prisoners. The Japanese military did scant accounting of Japanese prisoners of war. It seems likely that no more than 20,000 were prisoners. Since the Japanese who surrendered after August 15, 1945, the last day of the war, did not technically count as POWs by the Allies. They are not included in any Allied figures.

The British War Office’s Directorate of Prisoners stated that 6,142 prisoners were held on May 25, 1945. This number increased by the end of the war and when prisoners held by Australia and New Zealand are added to it, the number increased to more than 7,000. As of June 14, 1945, 806 Japanese military and naval prisoners were held at Featherston Camp, near Wellington, New Zealand. Before that date, forty-eight prisoners were killed when an officer led an assault against their captors. This camp had a hospital staffed by physicians; prisoners worked part of each day; and they were paid for their work. Their diet was good and their food was plentiful. They had dental care. The International Committee of the Red Cross provided golf clubs, model airplanes, ping pong tables and 500 dictionaries for Featherston prisoners. After they returned home, the senior Japanese officer wrote to the General Officer Commanding of the New Zealand Military Forces, thanking him for “the just and considerate treatment they had received.”

A Court of Inquiry was convened and decided that the Japanese prisoners were responsible for the deaths. The Japanese Government’s protest was sent to London where the Far Eastern Department of the Foreign Office warned that if Japanese prisoners were killed in Commonwealth camps, then the lives of British and Commonwealth prisoners in Japanese POW camps would be at great risk of retaliatory actions. As the Allies learned, nothing would stop the unending deaths of their forces in Japanese camps. Later, another fifty Japanese prisoners died in another assault at Featherston Camp.

What is known about American treatment of Japanese prisoners is largely anecdotal. Many anecdotes are about end-of-war happenings: at Bougainville, an island off New Guinea, a few Japanese waited to surrender at an airstrip. Two Allied airmen landed in a small planes. They taxied their plane to the Japanese, shot them, and then took off. Another anecdote concerns a postwar killing: a few American, British, Commonwealth, and Thai soldiers killed their Japanese captors. When you consider the atrocities committed by Japanese to Allied prisoners -- and the humiliating indignities, such as measuring penises – it’s remarkable that many Japanese captors were not killed after the Japanese surrender. Torture was common.

The United States had relatively few prisoner of war camps. For the first eight months of the war, we had no victories in the Pacific, only losses. When we

began gaining victories and with them a small number of prisoners, we asked our British and Commonwealth Allies if they would hold the soldiers whom we captured. They generally accepted them, and the majority were transferred to their camps. We did not want to remove any of our ships from the Pacific to transport Japanese to the United States. (I anchor this information behind parenthesis because I choose to: an estimated 2,800 Americans were killed by so-called friendly fire; that is, they were killed unknowingly by American firepower. This is what happened. Our prisoners were shipped to Japan on an estimated twenty-five transports, all them carrying no Red Cross identity – or any other. More than half of them were sunk by our submarines in the South China Sea. The estimates were arrived at from various allied sources. In one instance, a wolfpack of three American submarines attacked a convoy of Japanese ships, sinking a few of them. When they picked up more than 200 American survivors, they found out that the two transports on which the survivors were from, carried a total of 2,200 Allied prisoners. Australian journalist, in an article in Naval History {October 2004), notes that one of the submarines, the Pampanito, is now on view at Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco. Whether these American prisoners are included in the overall account, I don’t know. Somehow, I doubt it.)

With the approval and consent of the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and China, President Truman appointed General Douglas MacArthur the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers in the Pacific, on August 13, 1945. MacArthur issued an order on January 19, 1946, creating the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. The Charter delineated the scope, powers and jurisdiction of the Tribunal; and it dealt with the identification, apprehension, trial and punishment since the of major Far Eastern war criminals. The judges were high officials of the United States and our Allied nations, including Great Britain, Australia, Canada, China, Philippine Islands, Soviet Union, Netherlands, France and India.

The Charter stated: “The American member of a military tribunal trying persons accused with violations of the laws of war is not bound by the specific requirements of the United States Constitution and the Articles of War since the Supreme Court has decided that neither constitutional safeguards nor Articles of War apply in such proceedings (ex parte Quirin, 317 U. S. 1; In re Yamashita, February 4, 1946).

Tribunals for A, B and C Class war criminals were conducted between October 1945 and April 1951 in forty-nine locations in the Asia-Pacific region, including Manila, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Ribaul, Singapore and Yokahoma. A total of 5,379 Japanese; 173 Formosans; and 148 Koreans were tried. Of the total number, 984 were sentenced to death; 475 were sentenced to life imprisonment; and 2,944 were sentenced to lesser terms. Of twenty-eight Japanese war leaders indicted as Class A war criminals, twenty-five were found guilty. The Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal declared one defendant insane, and two others died before their trials. The Australian Government tried, without success, to have the Tribunal try the paramount war criminal, Emperor Hirohito.

At Nuremberg, twenty-four Nazis were indicted and twenty-two were tried for their lives. Three of them did not stand trial; two were physically too ill to stand trial and one committed suicide.

A just and fair accounting must recognize that not all Japanese neither acted with any measure of cruelty toward their enemies nor did they have any feeling but repulsion toward their government’s actions during the war. When I was in China, there were several incidents that I heard about in which Japanese soldiers, sickened by the atrocities of their colleagues, managed to load trucks with armament of various sorts and deliver them to Chinese forces. A moral correction in our thinking is warranted. There were Japanese soldiers, high officials, diplomats and civilians who acted humanely, at great risk to themselves and their families at home in pursuing what they knew to be righteous conduct. Their actions are footnotes to history; but we must be aware of their feelings and responses. To blanket all Japanese with opprobrium is a mistake. I will mention a few exceptions. The people who were repelled by their nation’s atrocities ranged from ordinary ranks to the Royal Family, from women in Japan to diplomats in foreign countries.

Hirohito’s youngest brother, Prince Takahito Mikasa, was sent to China to observe Japan’s military operations. He observed a textbook of torture. He happened to be at Nanking in the winter of 1937, when the Japanese army invaded the city. On the first day, they killed no fewer than 42,000 civilians and soldiers. In a three-month period, the Japanese slaughtered at least 369,366 people, including 150,000 soldiers, and raped 80,000 women. Nanking was China’s capital at the time; the massacre began on December 13, 1937.

An exact set of figures is impossible to pronounce. The Chinese Nationalist Government published a 100-volume history of the war from its new base on Formosa some twenty years after the end of the war. The official history states that 100,000 Chinese were killed during the massacre at Nanking. Japanese accounting for the number of Chinese prisoners of war killed ranges from 14,777 to 30,000. Professor Tian-wei Wu at Southern Illinois University places the total death toll at 340,000. A professor of history at Princeton, Ying-shi Yu, calculated that 354, 870 people were killed, including prisoners of war. For his data, Professor Yu used the statistics of ten burial societies in Nanking, including the Muslim Burial Team and the Advance Benevolence Society. The International Military Tribunal in Tokyo calibrated that 57,400 Chinese prisoners of war were killed by their Japanese captors. I believe the most wisely approximate figures are in a book, The Rape of Nanking: An Undeniable History in Photographs. by Shi Young and James Yin, published in 1997. Its writing, statistics, and photographs reveal hell.

Nanking was preceded in August 1937 by the slaughter of an estimated 300,000 people in Shanghai, in an orgy of rape and murder. Any female from the ages of ten to seventy was raped. Open-air copulation was common. The International Zone became a concentration camp; American, British and other nationals were killed in this presumed safety zone. The American hospital was ransacked. British and American students were taken from missionary schools, installed in Japanese brothels for their troops, and heard from no more. General Sugiyama attributed the success of these two operations to “some force even greater than God inspired our men.” Emperor Hirohito’s uncle, Prince Yasuhiko, was the commander of the Japanese Army’s Shanghai Expeditionary Force. He was responsible for Nanking and Shanghai, and was first based in Nanking. Yasuhiko issued this order to his Force, under his personal seal: “Kill all captives.”

Prince Takahito Mikasa observed the wholesale torture of the Chinese by the Japanese. He was appalled. He told the military leaders of his feelings, with no effect.

He wrote a memorandum about the conduct of the Japanese. When he returned to Tokyo, he handed his document to his brother, Emperor Hirohito. He urged his brother to bring a halt to the atrocities in China. The Emperor did nothing. The fact that a member of the Royal family was repelled by Japanese conduct and was willing to take his objection to the Emperor suggests that a few persons, at least, in the highest reaches of society were opposed to their nation’s savage behaviour. As gorey as this description is about the events at Nanking and Shanghai, it is just to acknowledge that there were Japanese whose revulsion for the rude deaths equalled ours.

A leading Japanese newspaper, Asahi Shimbun, invited its readers to submit letters to the editor about their experiences during the war and their feelings about their nation’s activities during it. The newspaper received 4,000 letters and printed 1,100 of them. In his two-volume book, The Japanese Remember the Pacific War, Frank Gibney edited a selection of the letters, performing a valuable service in trying to reduce the runaway biases against the Japanese. His book illuminates the shame and loss that the writers felt during the war, whether it was on the front lines or in the civilian population at home. Most importantly, the book reveals the courage of those who tried to resist the government’s conduct.

Chiune Sugihara, Japan’s vice-consul in Kaunas, Lithuania, distinguished himself as Oskar Schindler did in Germany, by saving up to 4,000 Lithuanian and Polish lives. During August 1940, he issued transit visas to them to travel to Japan. The British, French and American governments did not allow their their vice-consuls in Kaunas to issue transit visas.

All Americans should know that Japanese-American servicemen distinguished themselves during the war. They won more than their share of American decorations for their achievements in combat, including the Medal of Honor, the Distinguished Service Cross, the Silver Star, the Bronze Star and the Purple Heart. The most most decorated unit in the American army, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, fought in Italy, France and Germany. They fought with Merrill’s Mauraders in Burma. They fought behind Japanese lines in China, with the Office of Strategic Services. They participated in many of the toughest Pacific landings, including Iwo Jima and Saipan. The great majority of captured Nisei were killed. The parents and siblings of our Nisei were held throughout the war in internment camps in the United States.

Beyond a doubt, the Japanese acted with unusual cruelty during the war. But we Americans should not hide behind a seemingly racist gene in our undivided, singular condemnation of the wartime Japanese. The fact is that both Germany and Russia far exceeded the human destruction caused by the Japanese in the Second World War and in other wars wars during the past century.

Earlier, I said the Japanese people were largely trapped in an ethos of savagery during World War II. The Germans, on the other hand, voted for Adolph Hitler in a free election. I suspect that what I’m saying is that if we severely detested Japan during the war, we should just as strongly detest Germany and Russia. Both nations were more violent and perverted in exterminating millions of human beings, including their own people, than Japan. That is an incontrovertible fact.

A day or two after Japan surrendered, I received two Japanese visitors in Hotien, my base near the coast. They were Colonel Tin Boon, the officer in command of about 9,500 soldiers in my area, and a non-commissioned aide. They bowed and saluted me. My interpreter, Shum Hay, said, “The colonel wants to surrender to you. He says he has the utmost respect for you and President Roosevelt.”

I had received a message from my headquarters ordering me not to accept the surrender of any Japanese. I was advised to tell them to surrender to the Chinese Nationalist Army. Since Shum had read the message, he said to me, “We can’t accept their surrender. We can’t feed them. We have no place to keep them. What should we do?”

“Tell Colonel Boon that the Chinese do not allow Americans to accept any surrender under any circumstance,” I said. “Tell him I’m sorry, and please ask him if he’d like to have tea with us.”

Shum spoke to Colonel Boon. “The Colonel says he would like to have tea with you.” We had tea with Boon and his aide. All the while, I was tempted to ask him why he didn’t have his men capture and kill Shum and me. This could have been done with ease at any time during my stay in occupied China. But I didn’t ask him. I’ve been sorry I didn’t ever since.

Question: Which nation conducted human vivisection, biological warfare, and used a crematory?

Question: Which nation killed more than a third of their prisoners of war?

Question: Which nation trained young, school-age girls to carry explosives in school satchels to use in blowing up enemy vehicles and in the process killing themselves?

The answer to all of these questions is Japan, a fact that grows dimmer in our knowledge with each passing year. Japan has never formally accepted its guilt, aside from a few perfunctory apologies. Japan has never admitted its atrocities and it is unlikely that it ever will. On a visit to Great Britain in 1968, Emperor Hirohito allowed his interpreter to say, “The Emperor is sorry.” A Prime Minister of Japan, Tomiichi Murayama, offered many years later his “heartfelt apologies” for his nation’s actions, mainly directed at causing physical damage and destruction to other nations in Asia. In a recent article in The New York Times about a group of goodhearted Japanese who toured a few wartime horror sites in Manchuria, a visitor said, “We Japanese have never been able to say we made a mistake.” Caught in an ethos of savagery during the war, the Japanese considered themselves as victims after the war ended.

I reveal a glimpse about myself and my interest in this subject before I immerse you in a varied though selective portion of Japan’s record of its treatment of prisoners of war. Few weeks go by when I don’t recall my experiences in China during the Second World War. As a sole American representative of the Office of Strategic Services, I served behind the lines in Japanese-occupied territory in Kwangtung Province, up the coast from Hong Kong. I employed about forty Chinese agents who gathered military, naval and political information in Japanese-held coastal towns. I was selected for this activity because I was too young (I was twenty-one) and inexperienced to be overly scared at being surrounded by Japanese forces. In fact, I wasn’t scared until a Chinese agent whom I knew was captured by the Japanese. After a few day’s captivity, he was forced to dig his own grave and he was buried alive in it. Thereafter, I slept with a .45 pistol. I carried two .45s during the day as well as a suicide pencil. I decided that I would probably use my suicide pencil if capture by the Japanese seemed imminent. Japanese soldiers regularly marauded for food in my area, killing Chinese farmers and raping their wives and daughters. My war ended sixty years ago, but my memories of it are still vivid.

Japan began its war against China on September 18, 1931, invading Manchuria with an army of 200,000. They took control of Muken in a four hour battle with Chinese forces. In Mukden and other locations, they took no prisoners. Instead, they killed soldiers and civilians with abandon. This initial action was a preview of how Japan would fight in Asia and the Pacific for the next fourteen years.

Our Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson protested and Japan acceded to a temporary peace accord. The League of Nations began studying the situation. It sent an investigative team to Manchuria headed by Viscount Lytton of Great Britain with members representing the United States, Great Britain, France, Germany and Italy. The team’s report that called for Japan to leave Manchuria was passed by the League by a vote of 42 to 1. Result: Japan remained in Manchuria, the industrial heartland of China. No nation intervened. The League of Nations exhibited its impotence.

Representatives of Emperor Hirohito signed the International Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, in Geneva, on July 27, 1929. Since the Japanese Parliament did not ratify the Convention, they had no legal obligation to abide by it, not that it would have, in any event. Beginning in Manchuria, the Japanese record in killing prisoners and civilians never abated, without change or remission, for the following thirteen years. Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere began its work without remorse or pity. Murder is murder: an inclusive policy was followed subsequently in Burma, Thailand, Malaya, Indochina, Singapore, Formosa, Hong Kong, New Guinea, Korea, Borneo, Sumatra, the Philippines, the Netherland East Indies, in Japan itself, and throughout the Pacific.

An experimental biological warfare program was initiated by the Japanese in Manchuria in the early 1930s, under the command of an Imperial Army physician, Lieutenant General, Shiro Ishii. At Ping Fan, a village near Harbin, the general and his staff constructed a facility for human experimentation and extinction, complete with laboratories and a crematory with a tall mast of a chimney like those at Auschwitz. The crematory was photographed during the war; at war’s end, it was destroyed by the Japanese. The facility was named Unit 731. In other war areas, outside Manchuria, it was called Unit 100, with operational bases in other areas and nations throughout the war. But Unit 731 was the precursor, and it conducted its work on civilians, soldiers and prisoners in Manchuria. The Unit killed thousands of Chinese and Russian residents in Manchuria, in and around Harbin and Mukden, some of them subject to vivisection. Sheldon H. Harris, an American historian, whose book, Factories od Death: Japanese Secret Biological Warfare, 1932-1945, and the American Cover-Up, recounts his twenty years of research into Japanese biological warfare in Manchuria and occupied China. He estimated that 250,000 civilians and 10,000 to 12,000 prisoners of warfare were killed. This number seems excessive; but, since no one else made eleven trips to China doing research on this topic, we’ll let it stand. The American cover-up relates to the fact that we wanted the Unit’s data (200,000 pages) for our own biological warfare experiments. We gained the data. Not a single member of the Unit was charged as a war criminal in the Tokyo trials. Two hundred Unit members were tried and convicted by the Russians in a war crimes trial in Siberia after the war.

More than a recondite footnote, it is pertinent to note that the Russian army killed 70,000, or more, Japanese troops in an incursion that the Japanese made in 1939 into Mongolia. The Russians employed planes and tanks.

Once the Second World War began, on December 7, 1941, Japan opened two major prisoner of war of camps for Americans in Mukden. Many American POWs were killed by staff members of Unit 731. American POWs from as far away as the Philippines were sent to Mukden, including General Wainwright, McArthur’s deputy, whom he had left in the Philippines.

On July 7, 1937, Japan began its invasion of China proper at the Marco Polo Bridge, near Peking. At the time, the Chinese government called this the War of Resistance and again appealed for help in stopping Japanese aggression. Our Secretary of State Cordell Hull delivered A speech on July 14, 1937, advocating international justice and Avoidance of the use of force as an instrument in promoting national Policy. Result: nothing happened. China also appealed to Great Britain for help. The British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlin, adopted his first appeasement policy, toward Japan. His priority was to maintain British interests in the Far East. Result: nothing happened. Four years later, the Second World War began at Pearl Harbor, and China became our ally in the all-out war against Japan.

Japan operated more than 250 prisoner of war camps throughout Asia and the Pacific. Japan’s treatment of prisoners of war of all nations is beyond imagination. It’s my desire to limit this account to selected incidents, to delineate the context in which many deaths occurred, and not to try to convey the entire, bloody record in detail. Still, the record is gruesome; it can be neither hidden nor minimized.

Emperor Hirohito approved the following order that was written by The Minister of War, the only Cabinet member who had direct access to him. It was sent to all commanders of POW camps and to the chiefs of staff in all areas. It was transmitted to them on August 1, 1944 by the Vice Minister of War. By the summer of 1944, we and are allies were starting to make progress in the war, and the Japanese knew it.

Under the present situation if there were more explosion (sic) or fire

a shelter for the time being could be had in nearby buildings such as

a school, a warehouse, or the like. However, at such a time as the

situation becomes urgent and it is extremely important, the POWs will

be concentrated and confined in their present location and under

heavy guard the preparation for the disposition will be made. (sic)

The time and method of this disposition are as follows:

The Time.

although the basic aim is to act under superior orders,

individual disposition may be made in the following

circumstances:

When an uprising of large numbers cannot be

surpressed without the use of firearms.

when escapes from the camp may turn into a

hostile fighting force.

(2) The Methods.

Whether they are destroyed individually or in

groups, or however it is done, with mass bombing,

poisonous smoke, poison, drowning, decapitation, or what,

dispose of them as the situation dictates.

In any case it is the aim not to allow the escape

of a single one, to annihilate them all, and not to

leave any traces.

An example of this order occurred in 1944 at a POW camp at Palawan in the Philippines. When an American plane appeared, the commander of the camp, whose American prisoners were building an airfield, rounded them up, put them in air raid shelters, and ordered his troops to pour gasoline over the shelters and ignite them. A few Americans who escaped from the shelters were shot. Nine men survived by jumping into the sea and swimming to a nearby island. One hundred and fifty Americans were burned to death. At a POW camp on Bangka Island, off Sumatra, the Japanese bayonneted twenty-one Australian nurses. This happened in 1942. In 1944, the Japanese killed American airmen at Truk, including the beheading of a U. S. Navy radioman. The radioman was then cooked and eaten. Dr. Chisato Ueno and Lieutenant General Joshio Tachibana and eleven others were and executed at a war crimes trial for the beheading and cannabalism of U. S. Navy airmen. More than 125 Americans were beheaded during the war. An Indian prisoner of war in New Guinea said at a war crimes trial, “At this stage the Japanese started selecting prisoners and every day one prisoner was taken out and killed and eaten by the Japanese. I personally saw this happen and about one hundred prisoners were eaten at this place by the Japanese. Those selected were taken to a hut where flesh was cut from their bodies while they were alive and they were thrown into a ditch while they were still alive and where they later died. While flesh was being cut from those selected, terrible cries and shrieks came from them and also from the ditch where they were later thrown.”

Using war crime records, Michael Goodwin wrote a book, Shobun: A Forgotten War Crime in the Pacific, about an American bomber crew whose plane crash landed in Japanese territory. The crew, of which his father was a member, was captured and then beheaded. Shobun means execute. The Sandakan Death March was aptly named. In the first death march, in January 1945, some 2,000 to 3,000 prisoners, mostly British and Australian, were killed. Their Japanese captors expected an invasion. In the second death march, in June and July 1945, six prisoners survived out of a total of almost 2,400.

American prisoners of war totalled 21,580. The number of them killed by the Japanese was 7,107, representing 32.9 percent of those held captive. The total number of Allies, including Americans, in POW camps was 140,000. Roughly 35,000 were killed. Ninety percent of the Burmese andThai prisoners were killed. In the European Theater, 1.3 percent of American prisoners in German camps were killed. The notion that Germany was any less brutal than Japan in its treatment of prisoners is dispelled by the fact that of about 2,800,000 out of a total of 7,800,000 Soviet prisoners died in Germany.

It is difficult to gain an accurate or even an approximate number of the total number of Japanese prisoners of war. General George C. Marshall estimated that there were 41,464 Japanese prisoners. The International Committee of the Red Cross recorded 15,849 prisoners. A Japanese historian, Ikuhiko, claimed there were 50,000 Japanese POWs, including those in China. Another historian, Ikeda Kiyoshi, estimated that there were about 20,000. Slightly more 200, he reported, were killed without provocation; that is, without uprisings in POW camps.

The difference in figures, while not unusually varied, is revealing overall for the small number of Japanese who surrendered. Surrender was not in their vocabulary or their military culture; besides, Japanese troops knew nothing about the Geneva Conventions dealing with prisoners. The Japanese military did scant accounting of Japanese prisoners of war. It seems likely that no more than 20,000 were prisoners. Since the Japanese who surrendered after August 15, 1945, the last day of the war, did not technically count as POWs by the Allies. They are not included in any Allied figures.

The British War Office’s Directorate of Prisoners stated that 6,142 prisoners were held on May 25, 1945. This number increased by the end of the war and when prisoners held by Australia and New Zealand are added to it, the number increased to more than 7,000. As of June 14, 1945, 806 Japanese military and naval prisoners were held at Featherston Camp, near Wellington, New Zealand. Before that date, forty-eight prisoners were killed when an officer led an assault against their captors. This camp had a hospital staffed by physicians; prisoners worked part of each day; and they were paid for their work. Their diet was good and their food was plentiful. They had dental care. The International Committee of the Red Cross provided golf clubs, model airplanes, ping pong tables and 500 dictionaries for Featherston prisoners. After they returned home, the senior Japanese officer wrote to the General Officer Commanding of the New Zealand Military Forces, thanking him for “the just and considerate treatment they had received.”

A Court of Inquiry was convened and decided that the Japanese prisoners were responsible for the deaths. The Japanese Government’s protest was sent to London where the Far Eastern Department of the Foreign Office warned that if Japanese prisoners were killed in Commonwealth camps, then the lives of British and Commonwealth prisoners in Japanese POW camps would be at great risk of retaliatory actions. As the Allies learned, nothing would stop the unending deaths of their forces in Japanese camps. Later, another fifty Japanese prisoners died in another assault at Featherston Camp.

What is known about American treatment of Japanese prisoners is largely anecdotal. Many anecdotes are about end-of-war happenings: at Bougainville, an island off New Guinea, a few Japanese waited to surrender at an airstrip. Two Allied airmen landed in a small planes. They taxied their plane to the Japanese, shot them, and then took off. Another anecdote concerns a postwar killing: a few American, British, Commonwealth, and Thai soldiers killed their Japanese captors. When you consider the atrocities committed by Japanese to Allied prisoners -- and the humiliating indignities, such as measuring penises – it’s remarkable that many Japanese captors were not killed after the Japanese surrender. Torture was common.

The United States had relatively few prisoner of war camps. For the first eight months of the war, we had no victories in the Pacific, only losses. When we

began gaining victories and with them a small number of prisoners, we asked our British and Commonwealth Allies if they would hold the soldiers whom we captured. They generally accepted them, and the majority were transferred to their camps. We did not want to remove any of our ships from the Pacific to transport Japanese to the United States. (I anchor this information behind parenthesis because I choose to: an estimated 2,800 Americans were killed by so-called friendly fire; that is, they were killed unknowingly by American firepower. This is what happened. Our prisoners were shipped to Japan on an estimated twenty-five transports, all them carrying no Red Cross identity – or any other. More than half of them were sunk by our submarines in the South China Sea. The estimates were arrived at from various allied sources. In one instance, a wolfpack of three American submarines attacked a convoy of Japanese ships, sinking a few of them. When they picked up more than 200 American survivors, they found out that the two transports on which the survivors were from, carried a total of 2,200 Allied prisoners. Australian journalist, in an article in Naval History {October 2004), notes that one of the submarines, the Pampanito, is now on view at Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco. Whether these American prisoners are included in the overall account, I don’t know. Somehow, I doubt it.)

With the approval and consent of the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and China, President Truman appointed General Douglas MacArthur the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers in the Pacific, on August 13, 1945. MacArthur issued an order on January 19, 1946, creating the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. The Charter delineated the scope, powers and jurisdiction of the Tribunal; and it dealt with the identification, apprehension, trial and punishment since the of major Far Eastern war criminals. The judges were high officials of the United States and our Allied nations, including Great Britain, Australia, Canada, China, Philippine Islands, Soviet Union, Netherlands, France and India.

The Charter stated: “The American member of a military tribunal trying persons accused with violations of the laws of war is not bound by the specific requirements of the United States Constitution and the Articles of War since the Supreme Court has decided that neither constitutional safeguards nor Articles of War apply in such proceedings (ex parte Quirin, 317 U. S. 1; In re Yamashita, February 4, 1946).

Tribunals for A, B and C Class war criminals were conducted between October 1945 and April 1951 in forty-nine locations in the Asia-Pacific region, including Manila, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Ribaul, Singapore and Yokahoma. A total of 5,379 Japanese; 173 Formosans; and 148 Koreans were tried. Of the total number, 984 were sentenced to death; 475 were sentenced to life imprisonment; and 2,944 were sentenced to lesser terms. Of twenty-eight Japanese war leaders indicted as Class A war criminals, twenty-five were found guilty. The Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal declared one defendant insane, and two others died before their trials. The Australian Government tried, without success, to have the Tribunal try the paramount war criminal, Emperor Hirohito.

At Nuremberg, twenty-four Nazis were indicted and twenty-two were tried for their lives. Three of them did not stand trial; two were physically too ill to stand trial and one committed suicide.

A just and fair accounting must recognize that not all Japanese neither acted with any measure of cruelty toward their enemies nor did they have any feeling but repulsion toward their government’s actions during the war. When I was in China, there were several incidents that I heard about in which Japanese soldiers, sickened by the atrocities of their colleagues, managed to load trucks with armament of various sorts and deliver them to Chinese forces. A moral correction in our thinking is warranted. There were Japanese soldiers, high officials, diplomats and civilians who acted humanely, at great risk to themselves and their families at home in pursuing what they knew to be righteous conduct. Their actions are footnotes to history; but we must be aware of their feelings and responses. To blanket all Japanese with opprobrium is a mistake. I will mention a few exceptions. The people who were repelled by their nation’s atrocities ranged from ordinary ranks to the Royal Family, from women in Japan to diplomats in foreign countries.

Hirohito’s youngest brother, Prince Takahito Mikasa, was sent to China to observe Japan’s military operations. He observed a textbook of torture. He happened to be at Nanking in the winter of 1937, when the Japanese army invaded the city. On the first day, they killed no fewer than 42,000 civilians and soldiers. In a three-month period, the Japanese slaughtered at least 369,366 people, including 150,000 soldiers, and raped 80,000 women. Nanking was China’s capital at the time; the massacre began on December 13, 1937.

An exact set of figures is impossible to pronounce. The Chinese Nationalist Government published a 100-volume history of the war from its new base on Formosa some twenty years after the end of the war. The official history states that 100,000 Chinese were killed during the massacre at Nanking. Japanese accounting for the number of Chinese prisoners of war killed ranges from 14,777 to 30,000. Professor Tian-wei Wu at Southern Illinois University places the total death toll at 340,000. A professor of history at Princeton, Ying-shi Yu, calculated that 354, 870 people were killed, including prisoners of war. For his data, Professor Yu used the statistics of ten burial societies in Nanking, including the Muslim Burial Team and the Advance Benevolence Society. The International Military Tribunal in Tokyo calibrated that 57,400 Chinese prisoners of war were killed by their Japanese captors. I believe the most wisely approximate figures are in a book, The Rape of Nanking: An Undeniable History in Photographs. by Shi Young and James Yin, published in 1997. Its writing, statistics, and photographs reveal hell.

Nanking was preceded in August 1937 by the slaughter of an estimated 300,000 people in Shanghai, in an orgy of rape and murder. Any female from the ages of ten to seventy was raped. Open-air copulation was common. The International Zone became a concentration camp; American, British and other nationals were killed in this presumed safety zone. The American hospital was ransacked. British and American students were taken from missionary schools, installed in Japanese brothels for their troops, and heard from no more. General Sugiyama attributed the success of these two operations to “some force even greater than God inspired our men.” Emperor Hirohito’s uncle, Prince Yasuhiko, was the commander of the Japanese Army’s Shanghai Expeditionary Force. He was responsible for Nanking and Shanghai, and was first based in Nanking. Yasuhiko issued this order to his Force, under his personal seal: “Kill all captives.”

Prince Takahito Mikasa observed the wholesale torture of the Chinese by the Japanese. He was appalled. He told the military leaders of his feelings, with no effect.

He wrote a memorandum about the conduct of the Japanese. When he returned to Tokyo, he handed his document to his brother, Emperor Hirohito. He urged his brother to bring a halt to the atrocities in China. The Emperor did nothing. The fact that a member of the Royal family was repelled by Japanese conduct and was willing to take his objection to the Emperor suggests that a few persons, at least, in the highest reaches of society were opposed to their nation’s savage behaviour. As gorey as this description is about the events at Nanking and Shanghai, it is just to acknowledge that there were Japanese whose revulsion for the rude deaths equalled ours.

A leading Japanese newspaper, Asahi Shimbun, invited its readers to submit letters to the editor about their experiences during the war and their feelings about their nation’s activities during it. The newspaper received 4,000 letters and printed 1,100 of them. In his two-volume book, The Japanese Remember the Pacific War, Frank Gibney edited a selection of the letters, performing a valuable service in trying to reduce the runaway biases against the Japanese. His book illuminates the shame and loss that the writers felt during the war, whether it was on the front lines or in the civilian population at home. Most importantly, the book reveals the courage of those who tried to resist the government’s conduct.

Chiune Sugihara, Japan’s vice-consul in Kaunas, Lithuania, distinguished himself as Oskar Schindler did in Germany, by saving up to 4,000 Lithuanian and Polish lives. During August 1940, he issued transit visas to them to travel to Japan. The British, French and American governments did not allow their their vice-consuls in Kaunas to issue transit visas.

All Americans should know that Japanese-American servicemen distinguished themselves during the war. They won more than their share of American decorations for their achievements in combat, including the Medal of Honor, the Distinguished Service Cross, the Silver Star, the Bronze Star and the Purple Heart. The most most decorated unit in the American army, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, fought in Italy, France and Germany. They fought with Merrill’s Mauraders in Burma. They fought behind Japanese lines in China, with the Office of Strategic Services. They participated in many of the toughest Pacific landings, including Iwo Jima and Saipan. The great majority of captured Nisei were killed. The parents and siblings of our Nisei were held throughout the war in internment camps in the United States.

Beyond a doubt, the Japanese acted with unusual cruelty during the war. But we Americans should not hide behind a seemingly racist gene in our undivided, singular condemnation of the wartime Japanese. The fact is that both Germany and Russia far exceeded the human destruction caused by the Japanese in the Second World War and in other wars wars during the past century.

Earlier, I said the Japanese people were largely trapped in an ethos of savagery during World War II. The Germans, on the other hand, voted for Adolph Hitler in a free election. I suspect that what I’m saying is that if we severely detested Japan during the war, we should just as strongly detest Germany and Russia. Both nations were more violent and perverted in exterminating millions of human beings, including their own people, than Japan. That is an incontrovertible fact.

A day or two after Japan surrendered, I received two Japanese visitors in Hotien, my base near the coast. They were Colonel Tin Boon, the officer in command of about 9,500 soldiers in my area, and a non-commissioned aide. They bowed and saluted me. My interpreter, Shum Hay, said, “The colonel wants to surrender to you. He says he has the utmost respect for you and President Roosevelt.”

I had received a message from my headquarters ordering me not to accept the surrender of any Japanese. I was advised to tell them to surrender to the Chinese Nationalist Army. Since Shum had read the message, he said to me, “We can’t accept their surrender. We can’t feed them. We have no place to keep them. What should we do?”

“Tell Colonel Boon that the Chinese do not allow Americans to accept any surrender under any circumstance,” I said. “Tell him I’m sorry, and please ask him if he’d like to have tea with us.”

Shum spoke to Colonel Boon. “The Colonel says he would like to have tea with you.” We had tea with Boon and his aide. All the while, I was tempted to ask him why he didn’t have his men capture and kill Shum and me. This could have been done with ease at any time during my stay in occupied China. But I didn’t ask him. I’ve been sorry I didn’t ever since.