The Best Spies Didn't Wear Suits

December 2004 Author:Charles Pinck | Dan Pinck

The New York Times

Before America entered World War II, the intelligence being given to President Franklin D. Roosevelt was incomplete and poorly analyzed by several independent agencies. These included the Office of Naval Intelligence; the Army's intelligence agency, called G2; the Federal Bureau of Investigation; and the intelligence services at the State Department. Much like today's bureaucracies, these agencies did not share information well. But unlike today, there was no centralized intelligence effort focused on foreign threats.

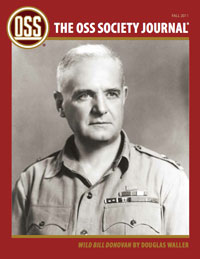

Enter William J. Donovan, known as Wild Bill, who was a World War I Medal of Honor winner, Wall Street lawyer, former United States attorney in Buffalo and 1932 Republican candidate for governor of New York. Although a member of the opposition party, Donovan got along well with Roosevelt, and the men shared an unfashionable belief that America's liberty was threatened by foreign powers.

In the late 30's, Donovan began traveling abroad and informally reporting his findings directly to Roosevelt. Eventually he convinced the president of the need for a centralized spying agency, and in July 1941 Roosevelt created a civilian agency within the White House to oversee American intelligence, naming Donovan to the new post of "coordinator of information."

Eleven months later, and half a year after Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt converted Donovan's group into the O.S.S. under a presidential order. In this the two faced great opposition, particularly from J. Edgar Hoover. (Donovan was later quoted as saying that his "greatest enemies were in Washington, not in Europe.")

Donovan reported directly to the president, even once bringing a silent pistol invented by the O.S.S. into the Oval Office and firing it. Roosevelt responded by telling Donovan he was the only Republican who would be allowed in the Oval Office with a gun.

Perhaps Donovan's greatest skill was his ability to recruit talented men and women from other fields, whether they came from the Ivy League, Wall Street or, believe it or not, prison. (After the war, Gen. William Quinn, then running the Strategic Services Unit, an interim organization created after the dissolution of the O.S.S. in 1945, was alerted by Treasury agents to the presence of master forgers in his ranks. Unknown to Quinn, Donovan had arranged for the release of these men from prison during the war to work for the O.S.S.)

Donovan was willing to try any ideas that he thought had potential and, what was more important, he had the power to act on them. He understood and accepted the inherent risks associated with intelligence work - often telling O.S.S. personnel that "you can't succeed without taking chances" - and was as willing to take responsibility for failures as for successes.

The O.S.S. under Donovan was not an insipid bureaucracy of career-minded professionals. It was a freewheeling organization devoted to finding effective ways of winning a war that imperiled the nation's future, a situation we find ourselves in once again. Donovan found formal decision-making and committees anathema to accomplishing his mission. Rather, he operated on good sense, instincts and experience - and gave the members of his staff great latitude to accomplish their missions as they saw fit.

Another unique feature of the organization was that it encompassed nearly all of the concerns that the C.I.A. and other intelligence organizations are engaged in today. For instance, the special operations branch, which would eventually be the model for the military's Special Forces, was then fully integrated into the other intelligence components. Donovan was also one of the first spy chiefs to recognize the importance of covert action and the need for "actionable intelligence" (information gathered and interpreted quickly enough that action can still be taken to change the situation).

When the war ended, President Harry Truman, who knew little about intelligence issues, disbanded the O.S.S. - only to realize his mistake two years later and create the Central Intelligence Agency. The new agency was different in several important ways, however. The O.S.S. had been an ad hoc group, what Donovan called "an unusual experiment" in unconventional means and methods against the enemy. From its very beginning, however, the C.I.A. was designed not as an experiment but as a permanent government institution. Many of its early leaders, excepting Walter Bedell Smith and Allen Dulles, were distinguished not for their intelligence experience but for their knack for political infighting.

As a peacetime organization, it was often compelled to pursue efficiency rather than effectiveness - it tended to play it safe when picking employees and projects. While this wasn't necessarily a fatal flaw during the cold war, a war of diplomacy and proxy armies in which data collection was often more important than covert action, it would be crippling in the hot war against terrorism.

Thus in the future our agencies should consider the somewhat haphazard way the O.S.S. chose people - unconventional warfare requires unconventional people. In addition, granting tremendous new powers to a "terrorism czar" will work only if that person is, like Donovan, truly independent and above the infighting we will certainly see from the Pentagon and other departments. And last, the new leader must have great leadership ability, intelligence experience and imagination.

Fisher Howe, a leading O.S.S. officer, once said that "if you define leadership as having a vision for an organization, and the ability to attract, motivate and guide followers to fulfill that mission, you have Bill Donovan in spades." In that sense, all the bureaucratic and legislative changes in the world won't matter if we don't find the right person for the job.

Before America entered World War II, the intelligence being given to President Franklin D. Roosevelt was incomplete and poorly analyzed by several independent agencies. These included the Office of Naval Intelligence; the Army's intelligence agency, called G2; the Federal Bureau of Investigation; and the intelligence services at the State Department. Much like today's bureaucracies, these agencies did not share information well. But unlike today, there was no centralized intelligence effort focused on foreign threats.

Enter William J. Donovan, known as Wild Bill, who was a World War I Medal of Honor winner, Wall Street lawyer, former United States attorney in Buffalo and 1932 Republican candidate for governor of New York. Although a member of the opposition party, Donovan got along well with Roosevelt, and the men shared an unfashionable belief that America's liberty was threatened by foreign powers.

In the late 30's, Donovan began traveling abroad and informally reporting his findings directly to Roosevelt. Eventually he convinced the president of the need for a centralized spying agency, and in July 1941 Roosevelt created a civilian agency within the White House to oversee American intelligence, naming Donovan to the new post of "coordinator of information."

Eleven months later, and half a year after Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt converted Donovan's group into the O.S.S. under a presidential order. In this the two faced great opposition, particularly from J. Edgar Hoover. (Donovan was later quoted as saying that his "greatest enemies were in Washington, not in Europe.")

Donovan reported directly to the president, even once bringing a silent pistol invented by the O.S.S. into the Oval Office and firing it. Roosevelt responded by telling Donovan he was the only Republican who would be allowed in the Oval Office with a gun.

Perhaps Donovan's greatest skill was his ability to recruit talented men and women from other fields, whether they came from the Ivy League, Wall Street or, believe it or not, prison. (After the war, Gen. William Quinn, then running the Strategic Services Unit, an interim organization created after the dissolution of the O.S.S. in 1945, was alerted by Treasury agents to the presence of master forgers in his ranks. Unknown to Quinn, Donovan had arranged for the release of these men from prison during the war to work for the O.S.S.)

Donovan was willing to try any ideas that he thought had potential and, what was more important, he had the power to act on them. He understood and accepted the inherent risks associated with intelligence work - often telling O.S.S. personnel that "you can't succeed without taking chances" - and was as willing to take responsibility for failures as for successes.

The O.S.S. under Donovan was not an insipid bureaucracy of career-minded professionals. It was a freewheeling organization devoted to finding effective ways of winning a war that imperiled the nation's future, a situation we find ourselves in once again. Donovan found formal decision-making and committees anathema to accomplishing his mission. Rather, he operated on good sense, instincts and experience - and gave the members of his staff great latitude to accomplish their missions as they saw fit.

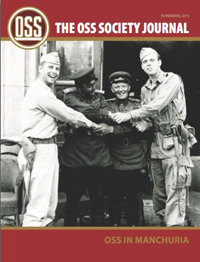

Another unique feature of the organization was that it encompassed nearly all of the concerns that the C.I.A. and other intelligence organizations are engaged in today. For instance, the special operations branch, which would eventually be the model for the military's Special Forces, was then fully integrated into the other intelligence components. Donovan was also one of the first spy chiefs to recognize the importance of covert action and the need for "actionable intelligence" (information gathered and interpreted quickly enough that action can still be taken to change the situation).

When the war ended, President Harry Truman, who knew little about intelligence issues, disbanded the O.S.S. - only to realize his mistake two years later and create the Central Intelligence Agency. The new agency was different in several important ways, however. The O.S.S. had been an ad hoc group, what Donovan called "an unusual experiment" in unconventional means and methods against the enemy. From its very beginning, however, the C.I.A. was designed not as an experiment but as a permanent government institution. Many of its early leaders, excepting Walter Bedell Smith and Allen Dulles, were distinguished not for their intelligence experience but for their knack for political infighting.

As a peacetime organization, it was often compelled to pursue efficiency rather than effectiveness - it tended to play it safe when picking employees and projects. While this wasn't necessarily a fatal flaw during the cold war, a war of diplomacy and proxy armies in which data collection was often more important than covert action, it would be crippling in the hot war against terrorism.

Thus in the future our agencies should consider the somewhat haphazard way the O.S.S. chose people - unconventional warfare requires unconventional people. In addition, granting tremendous new powers to a "terrorism czar" will work only if that person is, like Donovan, truly independent and above the infighting we will certainly see from the Pentagon and other departments. And last, the new leader must have great leadership ability, intelligence experience and imagination.

Fisher Howe, a leading O.S.S. officer, once said that "if you define leadership as having a vision for an organization, and the ability to attract, motivate and guide followers to fulfill that mission, you have Bill Donovan in spades." In that sense, all the bureaucratic and legislative changes in the world won't matter if we don't find the right person for the job.