Breaking Bread; For Teen Spy, A Little Trouble in Big China

August 2003

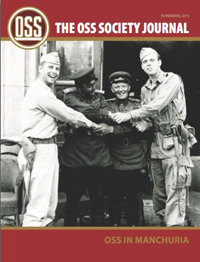

Some of the anecdotes he's weaving are recorded in his new book, "Journey to Peking," a delightful, insightful, and playful memoir about his 18 months in China as a secret agent for the Office of Strategic Services, the predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency.

"A lot of people will be pleased," he says, and then puckishly adds, "and a lot of people will say: 'Who's Dan Pinck?' "

A good question.

Pinck, now 79, was a spy to defy the stereotype, not as bold as Herb Philbrick in "I Led Three Lives" nor as altruistic as William Holden in "Counterfeit Traitor" - and never as hedonistic as James Bond in "Diamonds Are Forever," which is to say that Pinck was never dressed by a London tailor, never ordered a martini shaken, and never cavorted in exotic European capitals with wanton women.

Having enlisted in the Army as a freshman at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Va., he was elated to receive orders to active duty on the very morning in 1942 that he was scheduled to take an exam in calculus, about which he says he didn't know beans and was certain to flunk.

"I much preferred to go off to war," he recalls, "than take that exam in calculus."

On his first day in the Army, when a sergeant woke him at 4:30, Pinck told the sergeant to go to hell, and as a result he spent his first day in the Army on KP (kitchen patrol).

For an image of Pinck in the Army, forget Rambo. Think of Joseph Heller's novel "Catch 22," about the madness of a military bureaucracy gone amok, and especially the character Yossarian, who was ineligible for a mental health discharge from combat because merely asking for one demonstrated that he was sane.

For example, having passed a test to become an air cadet, Pinck was advised that, to qualify, he'd have to have two bad teeth pulled. After the extractions, he was told the rules had changed and that he'd have to have perfect eyesight, too. He didn't, and so his career as an aviator ended before it started.

He was assigned to the Army Air Corps and sent to Miami Beach, where he lived in the penthouse of an Art Deco hotel, sometimes playing tennis, sometimes marching down Collins Boulevard, singing an Army song.

"War is hell," mutters his wife, Joan, who is sitting across the table and to whom he dedicated his book. "Lost in you I find, welcome places in my mind," the inscription reads.

Putting down his turkey sandwich, Pinck sings the ditty.

Had a girl in Baltimore,

Little Liza Jane.

She is there but I ain't no more,

Little Liza Jane.

And then: "Have you heard that one, Joan?"

"Yes," she says with the patience of a marble saint. "I've heard you sing it before."

Pinck trained in meteorology and communications and was sent to India, where one day he was assigned to the military police for a brothel-busting brigade.

"I didn't know what a brothel was, but the idea was that you'd go inside and if you saw Americans having sex, you were to tap them on the shoulder, get them out of there and arrest them," he says. "I made no arrests that day."

Meanwhile, his mother, not having heard from him in so long, wrote to General George C. Marshall to ask, "How is my son?"

As Pinck recalls, she received a letter from Marshall that said, in effect, "Your son is fine."

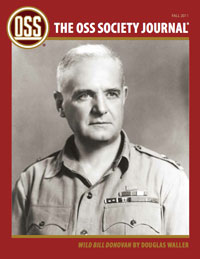

Bored with Army regimen, Pinck volunteered for the OSS, a unit founded by World War I hero William "Wild Bill" Donovan. The OSS needed someone to live in Hotien, a small Chinese village less than 900 miles from Japan. From Hotien, Pinck could send reports by Morse code four times a day about meteorological patterns and Japanese shipping in the South China Sea.

Although Pinck was only 19, had no experience in espionage, had never been to China, and did not speak the language, he won the assignment, he says, because his commanding officer lived not far from him in Bethesda, and they knew a lot of the same people.

Rather than send the teenager to his new assignment unprepared, the officer gave him two days indoctrination that consisted principally of teaching him how to insert a detonator into plastic to blow up something and how to use the dozen pencil-shaped, tubelike guns he was given, each with a single .22-caliber bullet, in case he was captured by the Japanese and wanted to commit suicide.

"They showed us how to insert the muzzle here," he says, opening his jaw and pointing to the roof of his mouth, "and then pull the trigger. I was puzzled as to why they gave me a dozen. I asked how many times I should commit suicide."

He was also given a .45 pistol and, to win the favor of the Chinese generals, a crate of condoms and a suitcase with $1 million in Chinese currency.

Handing money to the Chinese would wound their pride, warned his interpreter, Shum Hay. And so he engaged the generals in after-dinner poker games and proceeded to lose vast sums of money by, for example, drawing on inside straights.

"Shum was the best friend Dan ever had," says Joan, "and not because without him, Dan would have been shot or beheaded. Despite the language barrier, the chemistry was just right."

In Hotien, Pinck used his .45 pistol for target practice, perching a Japanese helmet on the stump of a tree.

"To my surprise," he says, "one day I actually hit the thing. Shot a hole right through it, and I was upset because I wanted to take that helmet home as a souvenir." He excuses himself, and from his study he retrieves the Japanese helmet with a bullet hole.

One of his aides, Lung Chiu Wah, had a beautiful girlfriend who seemed unusually curious about Pinck's Boy Scout manual.

"She very poor, almost prostitute," Lung said.

"You mean destitute," said Shum.

Suspecting the woman was a Japanese agent, Pinck pretended the Boy Scout manual was secret. When she disappeared, he tracked her to a tea shop and found pages of the manual and incriminating information meant for the Japanese.

"As a young man, I did a far better job than I could now or at any time later," says Pinck. "My ignorance protected me. Forrest Gump said it takes a lot of work to be stupid. I think that's pretty smart."

It was in China that Pinck began taking notes for the book that, in various incarnations, was rejected by more than 40 publishers until Pinck's son, Charles, a private investigator in Washington, persuaded the Naval Institute Press to publish it.

Now, he says, "I'm meeting a lot of new people."

The publisher, Naval Institute Press at Annapolis, sent copies to both George Bushes. From the president came a form letter. From his father, a personal note that praised the book.

Asked about the best story not in the book, Pinck recalled his going away party in Hotien.

"They served meatloaf. I had a bite, then another, didn't recognize the taste and asked what it was. They said it was a dog. For my party, they'd slaughtered a dog."

Discharged, he returned to Washington and Lee, then went to work at The New Yorker as assistant to the writer A.J. Liebling. He and Joan and four children lived in the South End for 23 years. Pinck is head of the New England Chapter of the OSS Society; his son heads the national organization.

Pinck also worked in administration at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in research at Harvard, and as a consultant in development in 14 African nations. He has written for such publications as "Encounter," "The American Scholar," and "The New Republic," often about Chinese-American relations.

"There were myths that the Chinese Communists were fighting the Japanese. They were no more fighting the Japanese than Cambridge is fighting Brookline. The communists were saving their energies for the postwar revolution. And they were killing as many Chinese and Americans as they were anyone else.

"There were scholars here, including till near the end of his life, John King Fairbank of Harvard, who was - I wouldn't say duped - but he'd been in the OSS in China and he thought Mao was an agrarian reformer. But anybody who kills [millions] of his own people is no agrarian and no reformer.

"The miracle is that when Deng Xiaoping came along and revamped the economic system and talked about property rights, this was remarkable because if China had gone into economic ruin, there'd have been another revolution."

Joan sets out cups with a CIA logo and lettering, and when hot coffee is added, the lettering changes to reflect the names of CIA directors. The cup was made in China.

In Pinck's library are hundreds of books about espionage and mementos of his time in China, including an American flag made by the people of Hotien that has red stripes where white should be and white where red should be.

Asked to write the first paragraph of his obituary, Pinck smiles, mischievously.

"Say: There are rumors Dan Pinck died, but they may not be true. You never can be sure with him."

"A lot of people will be pleased," he says, and then puckishly adds, "and a lot of people will say: 'Who's Dan Pinck?' "

A good question.

Pinck, now 79, was a spy to defy the stereotype, not as bold as Herb Philbrick in "I Led Three Lives" nor as altruistic as William Holden in "Counterfeit Traitor" - and never as hedonistic as James Bond in "Diamonds Are Forever," which is to say that Pinck was never dressed by a London tailor, never ordered a martini shaken, and never cavorted in exotic European capitals with wanton women.

Having enlisted in the Army as a freshman at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Va., he was elated to receive orders to active duty on the very morning in 1942 that he was scheduled to take an exam in calculus, about which he says he didn't know beans and was certain to flunk.

"I much preferred to go off to war," he recalls, "than take that exam in calculus."

On his first day in the Army, when a sergeant woke him at 4:30, Pinck told the sergeant to go to hell, and as a result he spent his first day in the Army on KP (kitchen patrol).

For an image of Pinck in the Army, forget Rambo. Think of Joseph Heller's novel "Catch 22," about the madness of a military bureaucracy gone amok, and especially the character Yossarian, who was ineligible for a mental health discharge from combat because merely asking for one demonstrated that he was sane.

For example, having passed a test to become an air cadet, Pinck was advised that, to qualify, he'd have to have two bad teeth pulled. After the extractions, he was told the rules had changed and that he'd have to have perfect eyesight, too. He didn't, and so his career as an aviator ended before it started.

He was assigned to the Army Air Corps and sent to Miami Beach, where he lived in the penthouse of an Art Deco hotel, sometimes playing tennis, sometimes marching down Collins Boulevard, singing an Army song.

"War is hell," mutters his wife, Joan, who is sitting across the table and to whom he dedicated his book. "Lost in you I find, welcome places in my mind," the inscription reads.

Putting down his turkey sandwich, Pinck sings the ditty.

Had a girl in Baltimore,

Little Liza Jane.

She is there but I ain't no more,

Little Liza Jane.

And then: "Have you heard that one, Joan?"

"Yes," she says with the patience of a marble saint. "I've heard you sing it before."

Pinck trained in meteorology and communications and was sent to India, where one day he was assigned to the military police for a brothel-busting brigade.

"I didn't know what a brothel was, but the idea was that you'd go inside and if you saw Americans having sex, you were to tap them on the shoulder, get them out of there and arrest them," he says. "I made no arrests that day."

Meanwhile, his mother, not having heard from him in so long, wrote to General George C. Marshall to ask, "How is my son?"

As Pinck recalls, she received a letter from Marshall that said, in effect, "Your son is fine."

Bored with Army regimen, Pinck volunteered for the OSS, a unit founded by World War I hero William "Wild Bill" Donovan. The OSS needed someone to live in Hotien, a small Chinese village less than 900 miles from Japan. From Hotien, Pinck could send reports by Morse code four times a day about meteorological patterns and Japanese shipping in the South China Sea.

Although Pinck was only 19, had no experience in espionage, had never been to China, and did not speak the language, he won the assignment, he says, because his commanding officer lived not far from him in Bethesda, and they knew a lot of the same people.

Rather than send the teenager to his new assignment unprepared, the officer gave him two days indoctrination that consisted principally of teaching him how to insert a detonator into plastic to blow up something and how to use the dozen pencil-shaped, tubelike guns he was given, each with a single .22-caliber bullet, in case he was captured by the Japanese and wanted to commit suicide.

"They showed us how to insert the muzzle here," he says, opening his jaw and pointing to the roof of his mouth, "and then pull the trigger. I was puzzled as to why they gave me a dozen. I asked how many times I should commit suicide."

He was also given a .45 pistol and, to win the favor of the Chinese generals, a crate of condoms and a suitcase with $1 million in Chinese currency.

Handing money to the Chinese would wound their pride, warned his interpreter, Shum Hay. And so he engaged the generals in after-dinner poker games and proceeded to lose vast sums of money by, for example, drawing on inside straights.

"Shum was the best friend Dan ever had," says Joan, "and not because without him, Dan would have been shot or beheaded. Despite the language barrier, the chemistry was just right."

In Hotien, Pinck used his .45 pistol for target practice, perching a Japanese helmet on the stump of a tree.

"To my surprise," he says, "one day I actually hit the thing. Shot a hole right through it, and I was upset because I wanted to take that helmet home as a souvenir." He excuses himself, and from his study he retrieves the Japanese helmet with a bullet hole.

One of his aides, Lung Chiu Wah, had a beautiful girlfriend who seemed unusually curious about Pinck's Boy Scout manual.

"She very poor, almost prostitute," Lung said.

"You mean destitute," said Shum.

Suspecting the woman was a Japanese agent, Pinck pretended the Boy Scout manual was secret. When she disappeared, he tracked her to a tea shop and found pages of the manual and incriminating information meant for the Japanese.

"As a young man, I did a far better job than I could now or at any time later," says Pinck. "My ignorance protected me. Forrest Gump said it takes a lot of work to be stupid. I think that's pretty smart."

It was in China that Pinck began taking notes for the book that, in various incarnations, was rejected by more than 40 publishers until Pinck's son, Charles, a private investigator in Washington, persuaded the Naval Institute Press to publish it.

Now, he says, "I'm meeting a lot of new people."

The publisher, Naval Institute Press at Annapolis, sent copies to both George Bushes. From the president came a form letter. From his father, a personal note that praised the book.

Asked about the best story not in the book, Pinck recalled his going away party in Hotien.

"They served meatloaf. I had a bite, then another, didn't recognize the taste and asked what it was. They said it was a dog. For my party, they'd slaughtered a dog."

Discharged, he returned to Washington and Lee, then went to work at The New Yorker as assistant to the writer A.J. Liebling. He and Joan and four children lived in the South End for 23 years. Pinck is head of the New England Chapter of the OSS Society; his son heads the national organization.

Pinck also worked in administration at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in research at Harvard, and as a consultant in development in 14 African nations. He has written for such publications as "Encounter," "The American Scholar," and "The New Republic," often about Chinese-American relations.

"There were myths that the Chinese Communists were fighting the Japanese. They were no more fighting the Japanese than Cambridge is fighting Brookline. The communists were saving their energies for the postwar revolution. And they were killing as many Chinese and Americans as they were anyone else.

"There were scholars here, including till near the end of his life, John King Fairbank of Harvard, who was - I wouldn't say duped - but he'd been in the OSS in China and he thought Mao was an agrarian reformer. But anybody who kills [millions] of his own people is no agrarian and no reformer.

"The miracle is that when Deng Xiaoping came along and revamped the economic system and talked about property rights, this was remarkable because if China had gone into economic ruin, there'd have been another revolution."

Joan sets out cups with a CIA logo and lettering, and when hot coffee is added, the lettering changes to reflect the names of CIA directors. The cup was made in China.

In Pinck's library are hundreds of books about espionage and mementos of his time in China, including an American flag made by the people of Hotien that has red stripes where white should be and white where red should be.

Asked to write the first paragraph of his obituary, Pinck smiles, mischievously.

"Say: There are rumors Dan Pinck died, but they may not be true. You never can be sure with him."