McCain Advocates a New Go-Get-'Em Spy Agency

July 2008

But his plan, a slap at the CIA, could create a whole new set of problems

By Kevin Whitelaw

US News & World Report

Sen. John McCain is taking on the Central Intelligence Agency on the campaign trail.

The attack is a subtle one, contained in his call for a new espionage agency patterned on the World War II-era Office of Strategic Services. McCain's proposal, which has yet to be debated publicly in the presidential campaign, is clearly an indictment of the CIA for being too bureaucratic and risk averse.

"In the spirit of the original OSS, this would be a small, nimble, can-do organization that would fight terrorist subversion across the world and in cyberspace," says McCain. "It could take risks that our bureaucracies today are afraid to take—risks such as infiltrating agents who lack diplomatic cover into terrorist organizations. It could even lead in the frontline efforts to rebuild failed states. A cadre of such undercover operatives would allow us to gain the intelligence on terrorist activities that we don't get today from our high-tech surveillance systems and from a CIA clandestine service that works almost entirely out of our embassies abroad."

The idea for a new spy organization is a direct outgrowth of a burgeoning Republican critique of the CIA, given new life by the controversy over the agency's analysis on Iraqi weapons of mass destruction. In the run-up to the U.S. invasion of Iraq, proponents of the war blasted the CIA for not being able to find evidence of Iraqi weapons of mass destruction. The CIA took even more flak in the aftermath of the invasion for its shoddy prewar intelligence, when it turned out that Saddam Hussein no longer had any such WMDs.

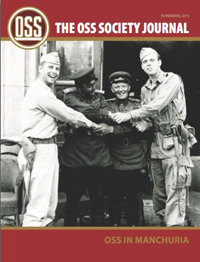

The McCain campaign has yet to issue a white paper detailing this new OSS, so many questions remain unanswered. The original OSS was a freewheeling organization of intelligence pioneers who operated with little oversight and whose primary mission was conducting sabotage operations in war-torn Europe. Today, there is a massive intelligence community made up of 16 different agencies that employ more than 100,000 people.

By Kevin Whitelaw

US News & World Report

Sen. John McCain is taking on the Central Intelligence Agency on the campaign trail.

The attack is a subtle one, contained in his call for a new espionage agency patterned on the World War II-era Office of Strategic Services. McCain's proposal, which has yet to be debated publicly in the presidential campaign, is clearly an indictment of the CIA for being too bureaucratic and risk averse.

"In the spirit of the original OSS, this would be a small, nimble, can-do organization that would fight terrorist subversion across the world and in cyberspace," says McCain. "It could take risks that our bureaucracies today are afraid to take—risks such as infiltrating agents who lack diplomatic cover into terrorist organizations. It could even lead in the frontline efforts to rebuild failed states. A cadre of such undercover operatives would allow us to gain the intelligence on terrorist activities that we don't get today from our high-tech surveillance systems and from a CIA clandestine service that works almost entirely out of our embassies abroad."

The idea for a new spy organization is a direct outgrowth of a burgeoning Republican critique of the CIA, given new life by the controversy over the agency's analysis on Iraqi weapons of mass destruction. In the run-up to the U.S. invasion of Iraq, proponents of the war blasted the CIA for not being able to find evidence of Iraqi weapons of mass destruction. The CIA took even more flak in the aftermath of the invasion for its shoddy prewar intelligence, when it turned out that Saddam Hussein no longer had any such WMDs.

The McCain campaign has yet to issue a white paper detailing this new OSS, so many questions remain unanswered. The original OSS was a freewheeling organization of intelligence pioneers who operated with little oversight and whose primary mission was conducting sabotage operations in war-torn Europe. Today, there is a massive intelligence community made up of 16 different agencies that employ more than 100,000 people.

How would a new OSS avoid overlap with all those other agencies, which currently pursue many of the same tasks McCain lays out? In particular, how would the new agency relate to the CIA, which today has the primary responsibility for overseas human intelligence gathering? And how much oversight would be needed to prevent abuses by a brand-new organization with such a sweeping mandate to spy and conduct covert action?

Many veterans of the CIA also bristle at McCain's suggestion that the CIA is risk averse and operates "almost entirely" out of U.S. Embassies. The CIA has struggled to improve its ability to send personnel overseas on what it calls "nonofficial cover," where CIA officers pose as businessmen or other professionals to steal secrets without the protection of a diplomatic passport. But it has also dispatched hundreds of officers for long-term and dangerous assignments in war zones.

"The CIA has guys on the front lines every day in Iraq and Afghanistan, and they want to call them risk averse. I don't think so," fumes Burton Gerber, who served in the CIA's Clandestine Service for 39 years and was CIA chief of station in Sofia, Belgrade, and Moscow. "If you could read my classified memoir, you would see there were great risks I took, and that's true for everybody."

It also remains unclear how McCain's proposed organization would tackle so many different threats (terrorism, cybersecurity, failed states) while remaining small and nimble. McCain's concept is as sweeping as it is vague. "A modern-day OSS could draw together unconventional-warfare, civil-affairs, paramilitary and psychological-warfare specialists from the military together with covert-action operators from our intelligence agencies and experts in anthropology, advertising, foreign cultures, and numerous other disciplines from inside and outside government," he says.

An agency that potentially sprawls across so many areas would require plenty of its own bureaucracy to establish, manage, and support all those missions.

"As so many have before him, Senator McCain is trying to use a structural fix to solve what is fundamentally a leadership problem. Frankly, so much of what stymies us right now is bloody-minded bureaucracy in Washington—turf fights. It comes down to fighting about who is really in charge, which is quite stupid," says Robert Grenier, a former CIA chief of station in Pakistan who is now a managing director at the risk management firm Kroll Inc. "To suggest that we could eliminate that by creating a new organization to pull all those elements together is completely unrealistic and in the short term would be enormously destructive."

The mention of a new organization that would undertake covert action also raises the ugly specter of the CIA's abuses in the 1960s and 1970s. Traditionally, this is the area that has gotten the CIA into the most trouble.

The CIA used to have broader powers to conduct missions to topple governments (with doomed operations like the Bay of Pigs), assassinate foreign targets, and even eavesdrop illegally on Americans. After some of its worst abuses were exposed in the 1970s (along with embarrassing episodes like the CIA's attempt to hire a mobster to assassinate Castro and its failed plot to poison the toothbrush of a Congolese rebel leader), a new, more rigorous oversight regime was put in place, and assassinations were forbidden.

In recent years, the CIA has been authorized to capture—or kill—some of the most high-value terrorist targets, but these orders now require a presidential sign-off.

Many veterans of the CIA also bristle at McCain's suggestion that the CIA is risk averse and operates "almost entirely" out of U.S. Embassies. The CIA has struggled to improve its ability to send personnel overseas on what it calls "nonofficial cover," where CIA officers pose as businessmen or other professionals to steal secrets without the protection of a diplomatic passport. But it has also dispatched hundreds of officers for long-term and dangerous assignments in war zones.

"The CIA has guys on the front lines every day in Iraq and Afghanistan, and they want to call them risk averse. I don't think so," fumes Burton Gerber, who served in the CIA's Clandestine Service for 39 years and was CIA chief of station in Sofia, Belgrade, and Moscow. "If you could read my classified memoir, you would see there were great risks I took, and that's true for everybody."

It also remains unclear how McCain's proposed organization would tackle so many different threats (terrorism, cybersecurity, failed states) while remaining small and nimble. McCain's concept is as sweeping as it is vague. "A modern-day OSS could draw together unconventional-warfare, civil-affairs, paramilitary and psychological-warfare specialists from the military together with covert-action operators from our intelligence agencies and experts in anthropology, advertising, foreign cultures, and numerous other disciplines from inside and outside government," he says.

An agency that potentially sprawls across so many areas would require plenty of its own bureaucracy to establish, manage, and support all those missions.

"As so many have before him, Senator McCain is trying to use a structural fix to solve what is fundamentally a leadership problem. Frankly, so much of what stymies us right now is bloody-minded bureaucracy in Washington—turf fights. It comes down to fighting about who is really in charge, which is quite stupid," says Robert Grenier, a former CIA chief of station in Pakistan who is now a managing director at the risk management firm Kroll Inc. "To suggest that we could eliminate that by creating a new organization to pull all those elements together is completely unrealistic and in the short term would be enormously destructive."

The mention of a new organization that would undertake covert action also raises the ugly specter of the CIA's abuses in the 1960s and 1970s. Traditionally, this is the area that has gotten the CIA into the most trouble.

The CIA used to have broader powers to conduct missions to topple governments (with doomed operations like the Bay of Pigs), assassinate foreign targets, and even eavesdrop illegally on Americans. After some of its worst abuses were exposed in the 1970s (along with embarrassing episodes like the CIA's attempt to hire a mobster to assassinate Castro and its failed plot to poison the toothbrush of a Congolese rebel leader), a new, more rigorous oversight regime was put in place, and assassinations were forbidden.

In recent years, the CIA has been authorized to capture—or kill—some of the most high-value terrorist targets, but these orders now require a presidential sign-off.