In The Ruins of Empire: The Japanese Surrender And The Battle for Postwar Asia

March 2008 Author:Dan Pinck

By Ronald H. Spector

Random House, 2007

Reviewed by Dan Pinck

This book is difficult for me to assess and I don’t mind saying this. Mr. Spector is a historian with a commendable reputation. He has written six or seven books that skillfully illuminate past wars, including World War II and Vietnam. Given the wide-angle scope and boldness of the thesis in his new book, I’m puzzled by its execution and the style or manner in which picks at some important facts. In some respects, his history is excitingly sound and in other respects, it’s somewhat scattered. I add that it’s possible that his book demolishes some of my thoughts about war and peace in Asia, and it dumps some of assumptions in a waste paper basket. But never mind. This goes with the territory of anyone who tries to capture China during the Second World War, as well as before and after it. When you add French Indochina, Great Britain, and the Netherlands to the mix, and Japan after their surrender, you’ve got an imposing swath of history. How to pick and choose? In this review, I propose to suggest what the context is, not to cover the entire, postwar geopolitical and military history of Asia. That’s a complex task for me. I expect I will concentrate on mainland China, with a few excursions to other nations. Along the way, I will undoubtedly reveal some of my eccentricities and biases.

Random House, 2007

Reviewed by Dan Pinck

This book is difficult for me to assess and I don’t mind saying this. Mr. Spector is a historian with a commendable reputation. He has written six or seven books that skillfully illuminate past wars, including World War II and Vietnam. Given the wide-angle scope and boldness of the thesis in his new book, I’m puzzled by its execution and the style or manner in which picks at some important facts. In some respects, his history is excitingly sound and in other respects, it’s somewhat scattered. I add that it’s possible that his book demolishes some of my thoughts about war and peace in Asia, and it dumps some of assumptions in a waste paper basket. But never mind. This goes with the territory of anyone who tries to capture China during the Second World War, as well as before and after it. When you add French Indochina, Great Britain, and the Netherlands to the mix, and Japan after their surrender, you’ve got an imposing swath of history. How to pick and choose? In this review, I propose to suggest what the context is, not to cover the entire, postwar geopolitical and military history of Asia. That’s a complex task for me. I expect I will concentrate on mainland China, with a few excursions to other nations. Along the way, I will undoubtedly reveal some of my eccentricities and biases.

I choose to allow Mr. Spector to set the compass of where he’s heading in his own words. I’ve added my observations. The following excerpts are from his introduction:

“Americans are accustomed to thinking of World War II as having ended on August 14, 1945, when Japan surrendered unconditionally.”

MY COMMENT: I confess that I’m one of those roughly 200 million Americans who believes that World War II ended with Japan’s surrender. I have a copy of the surrender document. When I occasionally read it, I have no doubt that’s when the war officially ended. I’m also accustomed to thinking that World War I ended on November 11, 1918. And I recognize that the Versaille Treaty all but guaranteed Germany’s initiating World War II. The interim years might be seen as a Cold War.

“ That was the end of the war so far as most Americans were concerned. Yet on the mainland of Asia, in the vast arc of countries and territories stretching from Manchuria to Burma, peace was at best a brief interlude. In some parts of Asia, such as Java and southern Indochina, peace lasted less than two months. In China, a fragile and incomplete peace lasted less than a year. In northern Indochina, peace lasted about fifteen months, and in Korea, about three years. Indeed, 1945-46 in Asia may have appeared to many not as a time when war ended, but as a time when various protagonists switched sides.”

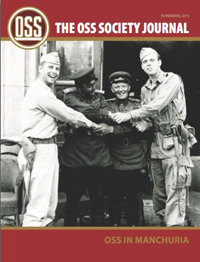

MY COMMENT: In fairness to Mr. Spectator, some wars were undoubtedly a continuation of what had been taking place, before and after World War II, especially in China. Japan invaded China’s province of Manchuria, with 200,000 troops, on September 18, 1931. They took control of Mukden in a four-hour battle. Japan began its invasion of China proper at the Marco Polo Bridge, near Peking, on July 7, 1937. After the Japanese surrender, the Nationalist Chinese fought the Communist Chinese until October 1, 1949. On that date, the Communists officially declared victory, in Peking, and the People’s Republic of China was born.

For the record, I believe that “a fragile and incomplete peace” after Japan’s surrender, lasted far less than a year. In fact, in parts of South China the Communists were sending teenagers, a few months after Japan’s surrender, into villages to inhabitants who lived on the main commercial paths. Later in this review, I will discuss China.

“Why did peace in Asia prove so elusive? What were the elements that contributed to the long postwar years of grim struggle during which many suffered far more than they had during World War II itself. With one exception, they were places in which things went disastrously wrong and gave birth to long-term problems that sometimes outlived the Cold War. This is largely a story about military occupations and their consequences. After the American experiences in Iraq it is unnecessary to explain that military occupations that follow on the areas of mainland Asia that had formed part of Japan’s empire.”

MY COMMENT: Our first responsibility in World War II in Asia, as it was in all theaters, was to win the war, to defeat our enemies, to save as many lives as possible, and to get home as soon as we could. To equate postwar problems in Asia to the absence of postwar military occupations is Mr. Spector’s primary thesis, I believe. Fighting didn’t stop in Asia after Japan’s surrender. It stopped in Japan because we occupied Japan. It did not stop in Asia because we went home as soon as we could. Peace brought war. Wars to end wars have long gone out of fashion. Lamentably, wars are a constant. No nation is so wise that it can forecast all of the consequences of its actions. Among President’s Eisenhower’s first actions was to end the war in Korea, and among his last was to make the unfortunate first steps that led to the Vietnam War. Were these wars generated by our failure in not providing a large army to sustain the Nationalist Chinese in their continuing war against the Chinese Communists, following the Japanese surrender and by our not building and sustaining an omnipotent military occupation in China, Indochina and Korea after Japan surrendered? Of course, I don’t know the answer to that. If I understand Mr. Spector correctly, and maybe I don’t, I wonder about his statement: “After the American experiences in Iraq it is unnecessary to explain that military occupations that follow on the areas of mainland Asia that had formed part of Japan’s empire.”

MY COMMENT: This puzzles me. I don’t know the answer; and I don’t know the question. But his challenge to conventional thinking is provocative. That’s for sure. Mr. Spector considers, I believe, that the nations which the Japanese conquered in Asia as components of their wartime empire. My problem with this is one of definition. Should a nation or territory that you’ve conquered by slaughtering tens of thousands of civilians and military personnel, throughout your occupation, be rightly defined as part of an empire? “The Shorter Oxford Dictionary” defines Empire in a number of different ways. “Supreme and extensive political dominion.” “An extensive territory (exp. an aggregate of many states) ruled over by an emporer or by a sovereign state.” “Great Britain with its colonies and dependencies; the British Empire.” In short, while you spend a few years killing a nation’s people, is the definition of “Empire” correct? I doubt it. Maybe, it’s a technicality. Is it correct to consider the nations that you conquer while the fighting occurs as part of your empire?

Mr. Spector is on target when he focuses on the pervasive problems of colonialism in Asia which were especially in the domains of the French, Dutch, and Great Britain. European imperialism was at the heart of the matter in Asia during and after the war. In 1942, President Roosevelt wrote to his son, Elliott, “Don’t think for a moment that Americans would be dying in the Pacific tonight if it hadn’t been for the short-sighted greed of the French and the British and the Dutch.” You may permit me for adding that if it weren’t for the Japanese, none of our Allies would have died in the Pacific and Asia. But Mr. Spector is precisely correct in identifying one of the major stumbling blocks to our efforts to reclaiming peace after the war. You ought to know that the Dutch was the most malevolent of the imperialists; the natives in Dutch-ruled territories, in general, at first welcomed the Japanese and would do almost anything to get out of the clutches of the Dutch. The same held true for the French and the British. And, in fact, we assisted them in recovering their Asian empires. An example is our helping Great Britain to return to Hong Kong before the Nationalist Chinese. The British presence in Hong Kong was analogous to a foreign nation owning New York. But we didn’t see it that way. The Nationalists wanted our help in flying their troops to Hong Kong as soon as Japan surrended. We did not do that, as you know. A day or two after the surrender, with our connivance, British ships landed in Hong Kong. And, as you may also know, we helped the French maintain their empire in Indochina. President Truman sent them military equipment to fight the Vietnamese.

Let me go back in history. When Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931, our Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson protested and Japan acceded to a temporary peace accord. He persuaded the League of Nations to send an investigative team to Manchuria headed by Viscount Lytton of Great Britain with members representing the United States, Great Britain, France, Germany and Italy. The team’s report that called for Japan to leave was passed by the League of Nations by a vote of 42 to 1. Result: Japan remained in Manchuria, the industrial heartland of China. No nation intervened. It’s interesting to note that a United States Congressman from Illinois published an article in H.L. Mencken’s magazine a year or two later in which he predicted that if we didn’t force the Japanese out of China, there would soon be a major war in China. Beginning in Manchuria, the Japanese record in killing prisoners and civilians never abated, without change or remission for the following thirteen years.

Japan’s Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere began its work without remorse or pity. Murder is murder: an inclusive policy was followed subsequently in Burma, Thailand, Malaya, Indochina, Singapore, Formosa, Hong Kong, New Guinea, Korea, Borneo, Sumatra, the Philippines, the Netherland East Indies, in Japan itself, and throughout the Pacific. When Japan began its invasion of China proper at the Marco Polo Bridge, in 1937, the Chinese again appealed for help. Our Secretary of State Cordell Hull delivered a speech on July 14, 1937, advocating international justics and avoidance of the use of force as an instrument in promoting national policy. Result: nothing happened. China then appealed to Great Britain for help. The British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlin adoped an appeasement policy toward Japan; his priority was to maintain British interests in the Far East. Result: nothing happened. Four years later, our entry into the Second World War began at Pearl Harbor, and China became our ally in the all-out war against Japan. History does keep a dear school.

“All of the soldiers who brought their various versions of liberations to the countries of Greater East Asia were members of famous military units, veterans of the most difficult campaigns of World War II. They were unprepared for their new role as occupiers and had at best an imperfect knowledge of the places they were going. They wanted most to go home. Their governments were often little better prepared, and these soldiers would soon become acquainted with the consequences of ignorance, inattention, and indecisiveness in London in London, Moscow and Washington.”

Here, it’s part of wisdom to invoke the aid of Pearl Buck, who had an intimate knowledge of China and was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize for Literature. She said, “There are no experts on China, only varying degrees of ignorance. I never knew of any group that considered itself occupiers in China. Let me add that maybe I’m wrong. Most soldiers I knew were generally ahead of most of their leaders in China, and Mr. Spector is absolutely right in saying they lived with the consequences of the deficiencies of their leaders in London and Washington. I know nothing about their leaders in Moscow. We had some ignorant boobs in high positions calling the shots in Washington. We had some able persons in China, including Generals Joseph Stilwell, George C. Marshall, Claire Chennault, head of the 14th Air Force and before we entered the war, the Flying Tigers, and Richard Heppner, the head of the OSS in China. They were outstanding and were often hemmed in by wildly incompetent and dangerous boobs, including Ambassador Patrick Jay Hurley, who was appointed by President Roosevelt. Marshall and Stilwell had both served in our army in Tientsin in the 1920s and they knew China as well as any Americans. “They wanted to go home,” Mr. Spector writes. They’d have to be nuts not to want to go home.” Assistant Secretary of State Dean Acheson cusses at the rush to send our troops home as soon as the war was concluded. To me, that’s weird.

One of the pleasures of Mr. Spector’s book are vignettes or snapshots of some of the major players and observations about events. I’ll ramble through a few of them with you. “On his first visit to Yenan, Hurley, resplendent in major general’s uniform with full medals, had greeted Mao-tung and other Communist leaders with a loud Choctaw war whoop as he disembarked from his plane....’Hurley was crazy,’ concluded John F. Melby, a State Department political officer in Chungking. ‘I think he was beginning to get a little senile....He wasn’t ambassador for very long [but] he sure raised a lot of hell while he was there.’”

“...Ho said that he could not understand why the principle of self-determination set forth in the Atlantic Charter and other Allied declarations should not apply to Vietnam and why the United States remained passive while the French and British re-erected the old Colonial system. The Chinese had given the back of the hand to the French in Hanoi, but Ho knew that in Chungking and Paris, negotiations were ongoing about trading an early end to occupation for French concessions in China.” I add that Ho copied the United States Declaration of Independence for his own Constitution.

“The colonels were War Department General Staff specialists on political-military issues but were not experts on Korea. Unlike Stettinius, however, they were able to locate it on the map, and they noted that the 38th parallel divided the Korean Peninsular in two.” (One of the colonels was Dean Rusk.)

General Marshall had the imposing and impossible task of persuading the Nationalist and Chinese Communists to join forces, to achieve a permanent settlement between them, to get ready to fight the USSR and not each other. Ambassador George C. Marshall wrote to his Washington liaison officer, “This is a hell of a problem.”

“Yet many of the occupations fell somewhat short of the avowed objective of liberating Asia from the Japanese. In China and Southeast Asia, the Allies employed thousands of Japanese soldiers and civilians as technicians, advisers, guards, auxiliaries, police, and sometimes combat roops against the local inhabitants they had come to “liberate.” A far smaller proportion of Japanese who threw in their lot with Southeast Asian nationalists played an important, perhaps critical, role in training, advising, and sometimes leading the anti-colonial forces.”

“An army general with long experience in Iraq recently observed that ‘every army of liberation has a half-life after which it turns into an army of occupation.”

“The British state that the Dutch are completely worthless with the formulation of policy and have shown themselves to be extreme cowards,’ wrote an OSS officer.’”

“Until a few months before the surrender, the Office of Strategic Services, widely referred to as ‘OSS’ had scarcely existed as a major contender in the bureaucratic Olympics incessantly played out in China’s wartime capitol, Chungking. The brainchild of Colonel William J. Donovan, a Wall Street lawyer, Republican political operator, and hero of World War I, OSS was conceived as a single agency that would coordinate the collection and analysis of foreign intelligence and conduct special operations such as commando raids and disinformation campaigns and work with partisan and guerrilla groups behind enemy lines. Older organizations like the Office of Naval Intelligence, the FBI, and the Army’s Military Intelligence Service viewed Donovan’s organization of former college professors, gangsters, corporate lawyers, and European emigres with suspicion.The two Pacific Commanders, General Douglas MacArthur and Admiral Chester Nimitz, barred Donovan’s organization from their theaters. Yet OSS proved its value in the North African campaign and in November 1942 Donovan received a broad charter from the Joint Chiefs of Staff to act as their agent for espionage, sabotage and psychological and guerrilla.”

The fact is that General Donovan and President Roosevelt cooked up the OSS. Donovan reported directly to the President. The JCS appointment was as much a bureaucratic convenience as anything else. And OSS representatives worked MacArthur’s and Nimitz’s domain as well as J. Edgar Hoover’s domain in South Africa, from which the OSS was also barred. The OSS was founded because of the gross inadequacies of intelligence services before Pearl Harbor. Roosevelt didn’t know it was coming and neither did the Office of Naval Intelligence or the Army’s Intelligence Service. After the war, General Donovan said he had more enemies in Washington during the war than he had overseas. The OSS is mentioned many times in the book; often it receives a passing grade. But that’s okay. Several times, the OSS is charged with being a publicity hound.

The history of China at war is a giant of a confusing mess and to uncover all of the complexities would take a hundred books. The Nationalists produced a history of the war that’s contained in one hundred books; and even in my amateur knowledge, it’s incomplete. Possibly, it would take a team of researchers decades to write an adequate history – not unlike the researchers who compiled the “Oxford English Dictionary” in about seventy years or so.

China, as we know, was a graveyard of reputations. But China was our ally in the war against Japan. And we did win the war, although China lost the war against the Communists. China received only 3.2 percent of all countries receiving our Lend-Lease material. That wasn’t much. Our leaders never made up their minds about what to do with China. General Chennault, the head of our 14th Air Force in China, and before our entry into World War II, the head of the Flying Tigers, observed after the war: “I always found the Chinese friendly and cooperative. The Japanese gave me a little trouble at time, but not very much. The British in Burma were quite difficult sometimes. But Washington gave me trouble night and day throughout the war.” How you can write a book dealing in large part with China and not mention General Chennault and General Joseph Stilwell in your index as Mr. Spector does, beats me. General Erwin Rommel is cited.

Chiang Kai-shek asked for and received foreign help long before World War II. From 1928 to 1938 received help from Germany. General Alexander von Falkenhausen, a Nazi, made sure that the Chinese learned how to use German weapons and that they learned how to march in the German goose-step. And we shouldn’t overlook other ingredients in the cockeyed world of Chiang Kai-shek. Chiang was a member of the fledgling Chinese Communist Party and he traveled to Moscow to gain Russia’s political and military help. With Stalin’s approval he came back to China with two million rubles. In 1927, with Lenin dead as well as the founder of the Chinese Nationalist Party, Sun Yat-sen, Chiang went on a mission to purge and kill Chinese Communists. He slaughtered thousands of Communists in Canton. To add to this bouillabaisse of history, Mao Ze-dong, who began his professional life as a librarian and ended it as the killer of 60 million of his own people, learned his craft of killing during the Second World War.

The evidence is that the war in China was an indisputable and direct benefit to us. There were roughly 60,000 Americans (a high estimate) in China. Roughly fewer than 4,000 Americans died in China (my estimate). This was fewer than the number of Americans killed at Iwo Jima. How did we gain from being in China? The answer is that more than 1 million Japanese soldiers remained in China during the latter part of the war. Without being tied up in China, it’s likely that the great majority of Japanese troops would have been sent to fight us in the Pacific. And many more Americans would have been killed.

“Americans are accustomed to thinking of World War II as having ended on August 14, 1945, when Japan surrendered unconditionally.”

MY COMMENT: I confess that I’m one of those roughly 200 million Americans who believes that World War II ended with Japan’s surrender. I have a copy of the surrender document. When I occasionally read it, I have no doubt that’s when the war officially ended. I’m also accustomed to thinking that World War I ended on November 11, 1918. And I recognize that the Versaille Treaty all but guaranteed Germany’s initiating World War II. The interim years might be seen as a Cold War.

“ That was the end of the war so far as most Americans were concerned. Yet on the mainland of Asia, in the vast arc of countries and territories stretching from Manchuria to Burma, peace was at best a brief interlude. In some parts of Asia, such as Java and southern Indochina, peace lasted less than two months. In China, a fragile and incomplete peace lasted less than a year. In northern Indochina, peace lasted about fifteen months, and in Korea, about three years. Indeed, 1945-46 in Asia may have appeared to many not as a time when war ended, but as a time when various protagonists switched sides.”

MY COMMENT: In fairness to Mr. Spectator, some wars were undoubtedly a continuation of what had been taking place, before and after World War II, especially in China. Japan invaded China’s province of Manchuria, with 200,000 troops, on September 18, 1931. They took control of Mukden in a four-hour battle. Japan began its invasion of China proper at the Marco Polo Bridge, near Peking, on July 7, 1937. After the Japanese surrender, the Nationalist Chinese fought the Communist Chinese until October 1, 1949. On that date, the Communists officially declared victory, in Peking, and the People’s Republic of China was born.

For the record, I believe that “a fragile and incomplete peace” after Japan’s surrender, lasted far less than a year. In fact, in parts of South China the Communists were sending teenagers, a few months after Japan’s surrender, into villages to inhabitants who lived on the main commercial paths. Later in this review, I will discuss China.

“Why did peace in Asia prove so elusive? What were the elements that contributed to the long postwar years of grim struggle during which many suffered far more than they had during World War II itself. With one exception, they were places in which things went disastrously wrong and gave birth to long-term problems that sometimes outlived the Cold War. This is largely a story about military occupations and their consequences. After the American experiences in Iraq it is unnecessary to explain that military occupations that follow on the areas of mainland Asia that had formed part of Japan’s empire.”

MY COMMENT: Our first responsibility in World War II in Asia, as it was in all theaters, was to win the war, to defeat our enemies, to save as many lives as possible, and to get home as soon as we could. To equate postwar problems in Asia to the absence of postwar military occupations is Mr. Spector’s primary thesis, I believe. Fighting didn’t stop in Asia after Japan’s surrender. It stopped in Japan because we occupied Japan. It did not stop in Asia because we went home as soon as we could. Peace brought war. Wars to end wars have long gone out of fashion. Lamentably, wars are a constant. No nation is so wise that it can forecast all of the consequences of its actions. Among President’s Eisenhower’s first actions was to end the war in Korea, and among his last was to make the unfortunate first steps that led to the Vietnam War. Were these wars generated by our failure in not providing a large army to sustain the Nationalist Chinese in their continuing war against the Chinese Communists, following the Japanese surrender and by our not building and sustaining an omnipotent military occupation in China, Indochina and Korea after Japan surrendered? Of course, I don’t know the answer to that. If I understand Mr. Spector correctly, and maybe I don’t, I wonder about his statement: “After the American experiences in Iraq it is unnecessary to explain that military occupations that follow on the areas of mainland Asia that had formed part of Japan’s empire.”

MY COMMENT: This puzzles me. I don’t know the answer; and I don’t know the question. But his challenge to conventional thinking is provocative. That’s for sure. Mr. Spector considers, I believe, that the nations which the Japanese conquered in Asia as components of their wartime empire. My problem with this is one of definition. Should a nation or territory that you’ve conquered by slaughtering tens of thousands of civilians and military personnel, throughout your occupation, be rightly defined as part of an empire? “The Shorter Oxford Dictionary” defines Empire in a number of different ways. “Supreme and extensive political dominion.” “An extensive territory (exp. an aggregate of many states) ruled over by an emporer or by a sovereign state.” “Great Britain with its colonies and dependencies; the British Empire.” In short, while you spend a few years killing a nation’s people, is the definition of “Empire” correct? I doubt it. Maybe, it’s a technicality. Is it correct to consider the nations that you conquer while the fighting occurs as part of your empire?

Mr. Spector is on target when he focuses on the pervasive problems of colonialism in Asia which were especially in the domains of the French, Dutch, and Great Britain. European imperialism was at the heart of the matter in Asia during and after the war. In 1942, President Roosevelt wrote to his son, Elliott, “Don’t think for a moment that Americans would be dying in the Pacific tonight if it hadn’t been for the short-sighted greed of the French and the British and the Dutch.” You may permit me for adding that if it weren’t for the Japanese, none of our Allies would have died in the Pacific and Asia. But Mr. Spector is precisely correct in identifying one of the major stumbling blocks to our efforts to reclaiming peace after the war. You ought to know that the Dutch was the most malevolent of the imperialists; the natives in Dutch-ruled territories, in general, at first welcomed the Japanese and would do almost anything to get out of the clutches of the Dutch. The same held true for the French and the British. And, in fact, we assisted them in recovering their Asian empires. An example is our helping Great Britain to return to Hong Kong before the Nationalist Chinese. The British presence in Hong Kong was analogous to a foreign nation owning New York. But we didn’t see it that way. The Nationalists wanted our help in flying their troops to Hong Kong as soon as Japan surrended. We did not do that, as you know. A day or two after the surrender, with our connivance, British ships landed in Hong Kong. And, as you may also know, we helped the French maintain their empire in Indochina. President Truman sent them military equipment to fight the Vietnamese.

Let me go back in history. When Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931, our Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson protested and Japan acceded to a temporary peace accord. He persuaded the League of Nations to send an investigative team to Manchuria headed by Viscount Lytton of Great Britain with members representing the United States, Great Britain, France, Germany and Italy. The team’s report that called for Japan to leave was passed by the League of Nations by a vote of 42 to 1. Result: Japan remained in Manchuria, the industrial heartland of China. No nation intervened. It’s interesting to note that a United States Congressman from Illinois published an article in H.L. Mencken’s magazine a year or two later in which he predicted that if we didn’t force the Japanese out of China, there would soon be a major war in China. Beginning in Manchuria, the Japanese record in killing prisoners and civilians never abated, without change or remission for the following thirteen years.

Japan’s Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere began its work without remorse or pity. Murder is murder: an inclusive policy was followed subsequently in Burma, Thailand, Malaya, Indochina, Singapore, Formosa, Hong Kong, New Guinea, Korea, Borneo, Sumatra, the Philippines, the Netherland East Indies, in Japan itself, and throughout the Pacific. When Japan began its invasion of China proper at the Marco Polo Bridge, in 1937, the Chinese again appealed for help. Our Secretary of State Cordell Hull delivered a speech on July 14, 1937, advocating international justics and avoidance of the use of force as an instrument in promoting national policy. Result: nothing happened. China then appealed to Great Britain for help. The British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlin adoped an appeasement policy toward Japan; his priority was to maintain British interests in the Far East. Result: nothing happened. Four years later, our entry into the Second World War began at Pearl Harbor, and China became our ally in the all-out war against Japan. History does keep a dear school.

“All of the soldiers who brought their various versions of liberations to the countries of Greater East Asia were members of famous military units, veterans of the most difficult campaigns of World War II. They were unprepared for their new role as occupiers and had at best an imperfect knowledge of the places they were going. They wanted most to go home. Their governments were often little better prepared, and these soldiers would soon become acquainted with the consequences of ignorance, inattention, and indecisiveness in London in London, Moscow and Washington.”

Here, it’s part of wisdom to invoke the aid of Pearl Buck, who had an intimate knowledge of China and was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize for Literature. She said, “There are no experts on China, only varying degrees of ignorance. I never knew of any group that considered itself occupiers in China. Let me add that maybe I’m wrong. Most soldiers I knew were generally ahead of most of their leaders in China, and Mr. Spector is absolutely right in saying they lived with the consequences of the deficiencies of their leaders in London and Washington. I know nothing about their leaders in Moscow. We had some ignorant boobs in high positions calling the shots in Washington. We had some able persons in China, including Generals Joseph Stilwell, George C. Marshall, Claire Chennault, head of the 14th Air Force and before we entered the war, the Flying Tigers, and Richard Heppner, the head of the OSS in China. They were outstanding and were often hemmed in by wildly incompetent and dangerous boobs, including Ambassador Patrick Jay Hurley, who was appointed by President Roosevelt. Marshall and Stilwell had both served in our army in Tientsin in the 1920s and they knew China as well as any Americans. “They wanted to go home,” Mr. Spector writes. They’d have to be nuts not to want to go home.” Assistant Secretary of State Dean Acheson cusses at the rush to send our troops home as soon as the war was concluded. To me, that’s weird.

One of the pleasures of Mr. Spector’s book are vignettes or snapshots of some of the major players and observations about events. I’ll ramble through a few of them with you. “On his first visit to Yenan, Hurley, resplendent in major general’s uniform with full medals, had greeted Mao-tung and other Communist leaders with a loud Choctaw war whoop as he disembarked from his plane....’Hurley was crazy,’ concluded John F. Melby, a State Department political officer in Chungking. ‘I think he was beginning to get a little senile....He wasn’t ambassador for very long [but] he sure raised a lot of hell while he was there.’”

“...Ho said that he could not understand why the principle of self-determination set forth in the Atlantic Charter and other Allied declarations should not apply to Vietnam and why the United States remained passive while the French and British re-erected the old Colonial system. The Chinese had given the back of the hand to the French in Hanoi, but Ho knew that in Chungking and Paris, negotiations were ongoing about trading an early end to occupation for French concessions in China.” I add that Ho copied the United States Declaration of Independence for his own Constitution.

“The colonels were War Department General Staff specialists on political-military issues but were not experts on Korea. Unlike Stettinius, however, they were able to locate it on the map, and they noted that the 38th parallel divided the Korean Peninsular in two.” (One of the colonels was Dean Rusk.)

General Marshall had the imposing and impossible task of persuading the Nationalist and Chinese Communists to join forces, to achieve a permanent settlement between them, to get ready to fight the USSR and not each other. Ambassador George C. Marshall wrote to his Washington liaison officer, “This is a hell of a problem.”

“Yet many of the occupations fell somewhat short of the avowed objective of liberating Asia from the Japanese. In China and Southeast Asia, the Allies employed thousands of Japanese soldiers and civilians as technicians, advisers, guards, auxiliaries, police, and sometimes combat roops against the local inhabitants they had come to “liberate.” A far smaller proportion of Japanese who threw in their lot with Southeast Asian nationalists played an important, perhaps critical, role in training, advising, and sometimes leading the anti-colonial forces.”

“An army general with long experience in Iraq recently observed that ‘every army of liberation has a half-life after which it turns into an army of occupation.”

“The British state that the Dutch are completely worthless with the formulation of policy and have shown themselves to be extreme cowards,’ wrote an OSS officer.’”

“Until a few months before the surrender, the Office of Strategic Services, widely referred to as ‘OSS’ had scarcely existed as a major contender in the bureaucratic Olympics incessantly played out in China’s wartime capitol, Chungking. The brainchild of Colonel William J. Donovan, a Wall Street lawyer, Republican political operator, and hero of World War I, OSS was conceived as a single agency that would coordinate the collection and analysis of foreign intelligence and conduct special operations such as commando raids and disinformation campaigns and work with partisan and guerrilla groups behind enemy lines. Older organizations like the Office of Naval Intelligence, the FBI, and the Army’s Military Intelligence Service viewed Donovan’s organization of former college professors, gangsters, corporate lawyers, and European emigres with suspicion.The two Pacific Commanders, General Douglas MacArthur and Admiral Chester Nimitz, barred Donovan’s organization from their theaters. Yet OSS proved its value in the North African campaign and in November 1942 Donovan received a broad charter from the Joint Chiefs of Staff to act as their agent for espionage, sabotage and psychological and guerrilla.”

The fact is that General Donovan and President Roosevelt cooked up the OSS. Donovan reported directly to the President. The JCS appointment was as much a bureaucratic convenience as anything else. And OSS representatives worked MacArthur’s and Nimitz’s domain as well as J. Edgar Hoover’s domain in South Africa, from which the OSS was also barred. The OSS was founded because of the gross inadequacies of intelligence services before Pearl Harbor. Roosevelt didn’t know it was coming and neither did the Office of Naval Intelligence or the Army’s Intelligence Service. After the war, General Donovan said he had more enemies in Washington during the war than he had overseas. The OSS is mentioned many times in the book; often it receives a passing grade. But that’s okay. Several times, the OSS is charged with being a publicity hound.

The history of China at war is a giant of a confusing mess and to uncover all of the complexities would take a hundred books. The Nationalists produced a history of the war that’s contained in one hundred books; and even in my amateur knowledge, it’s incomplete. Possibly, it would take a team of researchers decades to write an adequate history – not unlike the researchers who compiled the “Oxford English Dictionary” in about seventy years or so.

China, as we know, was a graveyard of reputations. But China was our ally in the war against Japan. And we did win the war, although China lost the war against the Communists. China received only 3.2 percent of all countries receiving our Lend-Lease material. That wasn’t much. Our leaders never made up their minds about what to do with China. General Chennault, the head of our 14th Air Force in China, and before our entry into World War II, the head of the Flying Tigers, observed after the war: “I always found the Chinese friendly and cooperative. The Japanese gave me a little trouble at time, but not very much. The British in Burma were quite difficult sometimes. But Washington gave me trouble night and day throughout the war.” How you can write a book dealing in large part with China and not mention General Chennault and General Joseph Stilwell in your index as Mr. Spector does, beats me. General Erwin Rommel is cited.

Chiang Kai-shek asked for and received foreign help long before World War II. From 1928 to 1938 received help from Germany. General Alexander von Falkenhausen, a Nazi, made sure that the Chinese learned how to use German weapons and that they learned how to march in the German goose-step. And we shouldn’t overlook other ingredients in the cockeyed world of Chiang Kai-shek. Chiang was a member of the fledgling Chinese Communist Party and he traveled to Moscow to gain Russia’s political and military help. With Stalin’s approval he came back to China with two million rubles. In 1927, with Lenin dead as well as the founder of the Chinese Nationalist Party, Sun Yat-sen, Chiang went on a mission to purge and kill Chinese Communists. He slaughtered thousands of Communists in Canton. To add to this bouillabaisse of history, Mao Ze-dong, who began his professional life as a librarian and ended it as the killer of 60 million of his own people, learned his craft of killing during the Second World War.

The evidence is that the war in China was an indisputable and direct benefit to us. There were roughly 60,000 Americans (a high estimate) in China. Roughly fewer than 4,000 Americans died in China (my estimate). This was fewer than the number of Americans killed at Iwo Jima. How did we gain from being in China? The answer is that more than 1 million Japanese soldiers remained in China during the latter part of the war. Without being tied up in China, it’s likely that the great majority of Japanese troops would have been sent to fight us in the Pacific. And many more Americans would have been killed.